by Joche Ojeda | Feb 16, 2026 | CLI, Github Copilot, SDK

Embedding GitHub Copilot Inside a DevExpress XAF Application

GitHub repository:

https://github.com/egarim/XafGitHubCopilot

Repository Structure (correct paths)

Startup (reference file you shared)

Blazor Startup:

/XafGitHubCopilot/XafGitHubCopilot.Blazor.Server/Startup.cs

Key Files (correct links)

Copilot SDK wiring (DI)

Tool calling (function calling)

XAF controllers

The Day I Integrated GitHub Copilot SDK Inside My XAF App (Part 1) | Joche Ojeda

by Joche Ojeda | Feb 9, 2026 | A.I

I wrote my previous article about closing the loop for agentic development earlier this week, although the ideas themselves have been evolving for several days. This new piece is simply a progress report: how the approach is working in practice, what I’ve built so far, and what I’m learning as I push deeper into this workflow.

Short version: it’s working.

Long version: it’s working really well — but it’s also incredibly token-hungry.

Let’s talk about it.

A Familiar Benchmark: The Activity Stream Problem

Whenever I want to test a new development approach, I go back to a problem I know extremely well: building an activity stream.

An activity stream is basically the engine of a social network — posts, reactions, notifications, timelines, relationships. It touches everything:

- Backend logic

- UI behavior

- Realtime updates

- State management

- Edge cases everywhere

I’ve implemented this many times before, so I know exactly how it should behave. That makes it the perfect benchmark for agentic development. If the AI handles this correctly, I know the workflow is solid.

This time, I used it to test the closing-the-loop concept.

The Current Setup

So far, I’ve built two main pieces:

- An MCP-based project

- A Blazor application implementing the activity stream

But the real experiment isn’t the app itself — it’s the workflow.

Instead of manually testing and debugging, I fully committed to this idea:

The AI writes, tests, observes, corrects, and repeats — without me acting as the middleman.

So I told Copilot very clearly:

- Don’t ask me to test anything

- You run the tests

- You fix the issues

- You verify the results

To make that possible, I wired everything together:

- Playwright MCP for automated UI testing

- Serilog logging to the file system

- Screenshot capture of the UI during tests

- Instructions to analyze logs and fix issues automatically

So the loop becomes:

write → test → observe → fix → retest

And honestly, I love it.

My Surface Is Working. I’m Not Touching It.

Here’s the funny part.

I’m writing this article on my MacBook Air.

Why?

Because my main development machine — a Microsoft Surface laptop — is currently busy running the entire loop by itself.

I told Copilot to open the browser and actually execute the tests visually. So it’s navigating the UI, filling forms, clicking buttons, taking screenshots… all by itself.

And I don’t want to touch that machine while it’s working.

It feels like watching a robot doing your job. You don’t interrupt it mid-task. You just observe.

So I switched computers and thought: “Okay, this is a perfect moment to write about what’s happening.”

That alone says a lot about where this workflow is heading.

Watching the Loop Close

Once everything was wired together, I let it run.

The agent:

- Writes code

- Runs Playwright tests

- Reads logs

- Reviews screenshots

- Detects issues

- Fixes them

- Runs again

Seeing the system self-correct without constant intervention is incredibly satisfying.

In traditional AI-assisted development, you often end up exhausted:

- The AI gets stuck

- You explain the issue

- It half-fixes it

- You explain again

- Something else breaks

You become the translator and debugger for the model.

With a self-correcting loop, that burden drops dramatically. The system can fail, observe, and recover on its own.

That changes everything.

The Token Problem (Yes, It’s Real)

There is one downside: this workflow is extremely token hungry.

Last month I used roughly 700% more tokens than usual. This month, and we’re only around February 8–9, I’ve already used about 200% of my normal limits.

Why so expensive?

Because the loop never sleeps:

- Test execution

- Log analysis

- Screenshot interpretation

- Code rewriting

- Retesting

- Iteration

Every cycle consumes tokens. And when the system is autonomous, those cycles happen constantly.

Model Choice Matters More Than You Think

Another important detail: not all models consume tokens equally inside Copilot.

Some models count as:

- 3× usage

- 1× usage

- 0.33× usage

- 0× usage

For example:

- Some Anthropic models are extremely good for testing and reasoning

- But they can count as 3× token usage

- Others are cheaper but weaker

- Some models (like GPT-4 Mini or GPT-4o in certain Copilot tiers) count as 0× toward limits

At some point I actually hit my token limits and Copilot basically said: “Come back later.”

It should reset in about 24 hours, but in the meantime I switched to the 0× token models just to keep the loop running.

The difference in quality is noticeable.

The heavier models are much better at:

- Debugging

- Understanding logs

- Self-correcting

- Complex reasoning

The lighter or free models can still work, but they struggle more with autonomous correction.

So model selection isn’t just about intelligence — it’s about token economics.

Why It’s Still Worth It

Yes, this approach consumes more tokens.

But compare that to the alternative:

- Sitting there manually testing

- Explaining the same bug five times

- Watching the AI fail repeatedly

- Losing mental energy on trivial fixes

That’s expensive too — just not measured in tokens.

I would rather spend tokens than spend mental fatigue.

And realistically:

- Models get cheaper every month

- Tooling improves weekly

- Context handling improves

- Local and hybrid options are evolving

What feels expensive today might feel trivial very soon.

MCP + Blazor: A Perfect Testing Ground

So far, this workflow works especially well for:

- MCP-based systems

- Blazor applications

- Known benchmark problems

Using a familiar problem like an activity stream lets me clearly measure progress. If the agent can build and maintain something complex that I already understand deeply, that’s a strong signal.

Right now, the signal is positive.

The loop is closing. The system is self-correcting. And it’s actually usable.

What Comes Next

This article is just a status update.

The next one will go deeper into something very important:

How to design self-correcting mechanisms for agentic development.

Because once you see an agent test, observe, and fix itself, you don’t want to go back to manual babysitting.

For now, though:

The idea is working. The workflow feels right. It’s token hungry. But absolutely worth it.

Closing the loop isn’t theory anymore — it’s becoming a real development style.

by Joche Ojeda | Jan 8, 2026 | C#, XAF

Async/await in C# is often described as “non-blocking,” but that description hides an important detail:

await is not just about waiting — it is about where execution continues afterward.

Understanding that single idea explains:

- why deadlocks happen,

- why

ConfigureAwait(false) exists,

- and why it *reduces* damage without fixing the root cause.

This article is not just theory. It’s written because this exact class of problem showed up again in real production code during the first week of 2026 — and it took a context-level fix to resolve it.

The Hidden Mechanism: Context Capture

When you await a task, C# does two things:

- It pauses the current method until the awaited task completes.

- It captures the current execution context (if one exists) so the continuation can resume there.

That context might be:

- a UI thread (WPF, WinForms, MAUI),

- a request context (classic ASP.NET),

- or no special context at all (ASP.NET Core, console apps).

This default behavior is intentional. It allows code like this to work safely:

var data = await LoadAsync();

MyLabel.Text = data.Name; // UI-safe continuation

But that same mechanism becomes dangerous when async code is blocked synchronously.

The Root Problem: Blocking on Async

Deadlocks typically appear when async code is forced into a synchronous shape:

var result = GetDataAsync().Result; // or .Wait()

What happens next:

- The calling thread blocks, waiting for the async method to finish.

- The async method completes its awaited operation.

- The continuation tries to resume on the original context.

- That context is blocked.

- Nothing can proceed.

💥 Deadlock.

This is not an async bug. This is a context dependency cycle.

The Blast Radius Concept

Blocking on async is the explosion.

The blast radius is how much of the system is taken down with it.

Full blast (default await)

- Continuation *requires* the blocked context

- The async operation cannot complete

- The caller never unblocks

- Everything stops

Reduced blast (ConfigureAwait(false))

- Continuation does not require the original context

- It resumes on a thread pool thread

- The async operation completes

- The blocking call unblocks

The original mistake still exists — but the damage is contained.

The real fix is “don’t block on async,”

but ConfigureAwait(false) reduces the blast radius when someone does.

What ConfigureAwait(false) Actually Does

await SomeAsyncOperation().ConfigureAwait(false);

This tells the runtime:

“I don’t need to resume on the captured context. Continue wherever it’s safe to do so.”

Important clarifications:

- It does not make code faster by default

- It does not make code parallel

- It does not remove the need for proper async flow

- It only removes context dependency

Why This Matters in Real Code

Async code rarely exists in isolation.

A method often awaits another method, which awaits another:

await AAsync();

await BAsync();

await CAsync();

If any method in that chain requires a specific context, the entire chain becomes context-bound.

That is why:

- library code must be careful,

- deep infrastructure layers must avoid context assumptions,

- and UI layers must be explicit about where context is required.

When ConfigureAwait(false) Is the Right Tool

Use it when all of the following are true:

- The method does not interact with UI state

- The method does not depend on a request context

- The method is infrastructure, library, or backend logic

- The continuation does not care which thread resumes it

This is especially true for:

- NuGet packages

- shared libraries

- data access layers

- network and IO pipelines

What It Is Not

ConfigureAwait(false) is not:

- a fix for bad async usage

- a substitute for proper async flow

- a reason to block on tasks

- something to blindly apply everywhere

It is a damage-control tool, not a cure.

A Real Incident: When None of the Usual Fixes Worked

First week of 2026.

The first task I had with the programmers in my office was to investigate a problem in a trading block. The symptoms looked like a classic async issue: timing bugs, inconsistent behavior, and freezes that felt “await-shaped.”

We did what experienced .NET teams typically do when async gets weird:

- Reviewed the full async/await chain end-to-end

- Double-checked the source code carefully (everything looked fine)

- Tried the usual “tools people reach for” under pressure:

.Wait().GetAwaiter().GetResult()- wrapping in

Task.Run(...)

- adding

ConfigureAwait(false)

- mixing combinations of those approaches

None of it reliably fixed the problem.

At that point it stopped being a “missing await” story. It became a “the model is right but reality disagrees” story.

One of the programmers, Daniel, and I went deeper. I found myself mentally replaying every async pattern I know — especially because I’ve written async-heavy code myself, including library work like SyncFramework, where I synchronize databases and deal with long-running operations.

That’s the moment where this mental model matters: it forces you to stop treating await like syntax and start treating it like mechanics.

The Actual Root Cause: It Was the Context

In the end, the culprit wasn’t which pattern we used — it was where the continuation was allowed to run.

This application was built on DevExpress XAF. In this environment, the “correct” continuation behavior is often tied to XAF’s own scheduling and application lifecycle rules. XAF provides a mechanism to run code in its synchronization context — for example using BlazorApplication.InvokeAsync, which ensures that continuations run where the framework expects.

Once we executed the problematic pipeline through XAF’s synchronization context, the issue was solved.

No clever pattern. No magical await. No extra parallelism.

Just: the right context.

And this is not unique to XAF. Similar ideas exist in:

- Windows Forms (UI thread affinity + SynchronizationContext)

- WPF (Dispatcher context)

- Any framework that requires work to resume on a specific thread/context

Why I’m Writing This

What I wanted from this experience is simple: don’t forget it.

Because what makes this kind of incident dangerous is that it looks like a normal async bug — and the internet is full of “four fixes” people cycle through:

- add/restore missing

await

- use

.Wait() / .Result

- wrap in

Task.Run()

- use

ConfigureAwait(false)

Sometimes those are relevant. Sometimes they’re harmful. And sometimes… they’re all beside the point.

In our case, the missing piece was framework context — and once you see that, you realize why the “blast radius” framing is so useful:

- Blocking is the explosion.

ConfigureAwait(false) contains damage when someone blocks.- If a framework requires a specific synchronization context, the fix may be to supply the correct context explicitly.

That’s what happened here. And that’s why I’m capturing it as live knowledge, not just documentation.

The Mental Model to Keep

- Async bugs are often context bugs

- Blocking creates the explosion

- Context capture determines the blast radius

ConfigureAwait(false) limits the damage- Proper async flow prevents the explosion entirely

- Frameworks may require their own synchronization context

- Correct async code can still fail in the wrong context

Async is not just about tasks. It’s about where your code is allowed to continue.

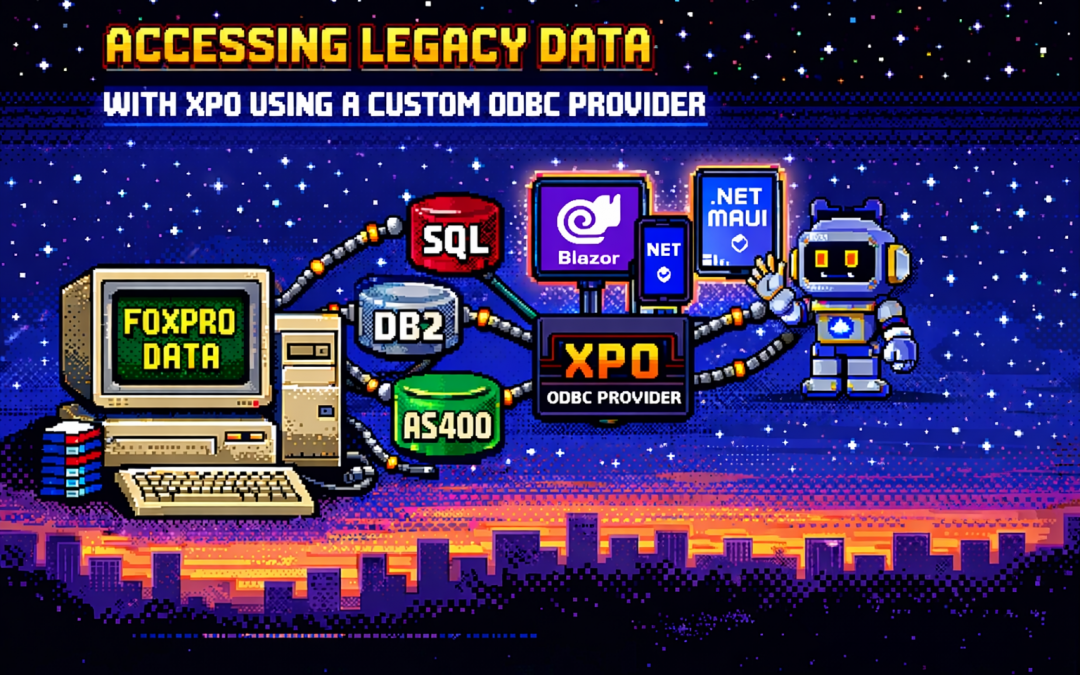

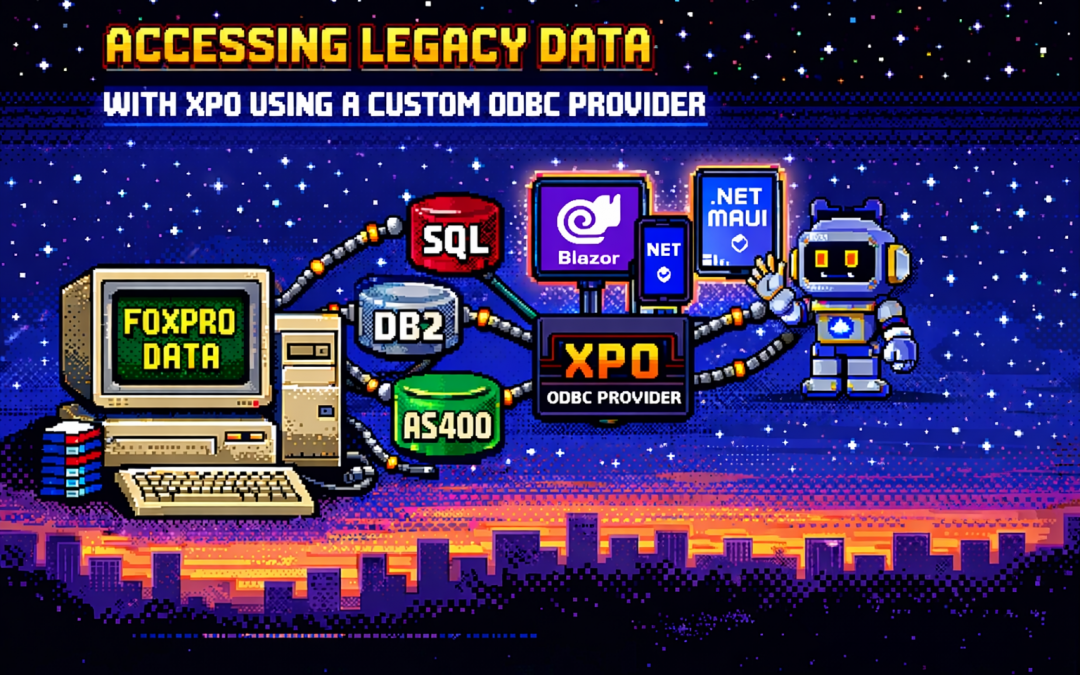

by Joche Ojeda | Dec 23, 2025 | ADO, ADO.NET, XPO

One of the recurring challenges in real-world systems is not building new software — it’s

integrating with software that already exists.

Legacy systems don’t disappear just because newer technologies are available. They survive because they work,

because they hold critical business data, and because replacing them is often risky, expensive, or simply not allowed.

This article explores a practical approach to accessing legacy data using XPO by leveraging ODBC,

not as a universal abstraction, but as a bridge when no modern provider exists.

The Reality of Legacy Systems

Many organizations still rely on systems built on technologies such as:

- FoxPro tables

- AS400 platforms

- DB2-based systems

- Proprietary or vendor-abandoned databases

In these scenarios, it’s common to find that:

- There is no modern .NET provider

- There is no ORM support

- There is an ODBC driver

That last point is crucial. ODBC often remains available long after official SDKs and providers have disappeared.

It becomes the last viable access path to critical data.

Why ORMs Struggle with Legacy Data

Modern ORMs assume a relatively friendly environment: a supported database engine, a known SQL dialect,

a compatible type system, and an actively maintained provider.

Legacy databases rarely meet those assumptions. As a result, teams are often forced to:

- Drop down to raw SQL

- Build ad-hoc data access layers

- Treat legacy data as a second-class citizen

This becomes especially painful in systems that already rely heavily on DevExpress XPO for persistence,

transactions, and domain modeling.

ODBC Is Not Magic — and That’s the Point

ODBC is often misunderstood.

Using ODBC does not mean:

- One provider works for every database

- SQL becomes standardized

- Type systems become compatible

Each ODBC-accessible database still has:

- Its own SQL dialect

- Its own limitations

- Its own data types

- Its own behavioral quirks

ODBC simply gives you a way in. It is a transport mechanism, not a universal language.

What an XPO ODBC Provider Really Is

When you implement an XPO provider on top of ODBC, you are not building a generic solution for all databases.

You are building a targeted adapter for a specific legacy system that happens to be reachable via ODBC.

This matters because ODBC is used here as a pragmatic trick:

- To connect to something you otherwise couldn’t

- To reuse an existing, stable access path

- To avoid rewriting or destabilizing legacy systems

The database still dictates the SQL dialect, supported features, and type system. Your provider must respect those constraints.

Why XPO Makes This Possible

XPO is not just an ORM — it is a provider-based persistence framework.

All SQL-capable XPO providers are built on top of a shared foundation, most notably:

ConnectionProviderSql

https://docs.devexpress.com/CoreLibraries/DevExpress.Xpo.DB.ConnectionProviderSql

This architecture allows you to reuse XPO’s core benefits:

- Object model

- Sessions and units of work

- Transaction handling

- Integration with domain logic

While customizing what legacy systems require:

- SQL generation

- Command execution

- Schema discovery

- Type mapping

Dialects and Type Systems Still Matter

Even when accessed through ODBC:

- FoxPro is not SQL Server

- DB2 is not PostgreSQL

- AS400 is not Oracle

Each system has its own:

- Date and time semantics

- Numeric precision rules

- String handling behavior

- Constraints and limits

An XPO ODBC provider must explicitly map database types, handle dialect-specific SQL,

and avoid assumptions about “standard SQL.” ODBC opens the door — it does not normalize what’s inside.

Real-World Experience: AS400 and DB2 in Production

This approach is not theoretical. Last year, we implemented a custom XPO provider using ODBC for

AS400 and DB2 systems in Mexico, where:

- No viable modern .NET provider existed

- The systems were deeply embedded in business operations

- ODBC was the only stable integration path

By introducing an XPO provider on top of ODBC, we were able to integrate legacy data into a modern .NET architecture,

preserve domain models and transactional behavior, and avoid rewriting or destabilizing existing systems.

The Hidden Advantage: Modern UI and AI Access

Once legacy data is exposed through XPO, something powerful happens: that data becomes immediately available to modern platforms.

- Blazor applications

- .NET MAUI mobile and desktop apps

- Background services

- Integration APIs

- AI agents and assistants

And you get this without rewriting the database, migrating the data, or changing the legacy system.

XPO becomes the adapter that allows decades-old data to participate in modern UI stacks, automated workflows,

and AI-driven experiences.

Why Not Just Use Raw ODBC?

Raw ODBC gives you rows, columns, and primitive values. XPO gives you domain objects, identity tracking,

relationships, transactions, and a consistent persistence model.

The goal is not to modernize the database. The goal is to modernize access to legacy data

so it can safely participate in modern architectures.

Closing Thought

An XPO ODBC provider is not a silver bullet. It will not magically unify SQL dialects, type systems, or database behavior.

But when used intentionally, it becomes a powerful bridge between systems that cannot be changed

and architectures that still need to evolve.

ODBC is the trick that lets you connect.

XPO is what makes that connection usable — everywhere, from Blazor UIs to AI agents.

by Joche Ojeda | Oct 16, 2025 | Events, Oqtane

OK, I’m still blocked from GitHub Copilot, so I still have more things to write about.

In this article, the topic that we’re going to see is the event system of Oqtane.For example, usually in most systems you want to hook up something when the application starts.

In XAF from Developer Express, which is my specialty (I mean, that’s the framework I really know well),

you have the DB Updater, which you can use to set up some initial data.

In Oqtane, you have the Module Manager, but there are also other types of events that you might need —

for example, when the user is created or when the user signs in for the first time.

So again, using the method that I explained in my previous article — the “OK, I have a doubt” method —

I basically let the guide of Copilot hike over my installation folder or even the Oqtane source code itself, and try to figure out how to do it.

That’s how I ended up using event subscribers.

In one of my prototypes, what I needed to do was detect when the user is created and then create some records in a different system

using that user’s information. So I’ll show an example of that type of subscriber, and I’ll actually share the

Oqtane Event Handling Guide here, which explains how you can hook up to system events.

I’m sure there are more events available, but this is what I’ve found so far and what I’ve tested.

I guess I’ll make a video about all these articles at some point, but right now, I’m kind of vibing with other systems.

Whenever I get blocked, I write something about my research with Oqtane.

Oqtane Event Handling Guide

Comprehensive guide to capturing and responding to system events in Oqtane

This guide explains how to handle events in Oqtane, particularly focusing on user authentication events (login, logout, creation)

and other system events. Learn to build modules that respond to framework events and create custom event-driven functionality.

Version: 1.0.0

Last Updated: October 3, 2025

Oqtane Version: 6.0+

Framework: .NET 9.0

1. Overview of Oqtane Event System

Oqtane uses a centralized event system based on the SyncManager that broadcasts events throughout the application when entities change.

This enables loose coupling between components and allows modules to respond to framework events without tight integration.

Key Components

- SyncManager — Central event hub that broadcasts entity changes

- SyncEvent — Event data containing entity information and action type

- IEventSubscriber — Interface for objects that want to receive events

- EventDistributorHostedService — Background service that distributes events to subscribers

Entity Changes → SyncManager → EventDistributorHostedService → IEventSubscriber Implementations

↓

SyncEvent Created → Distributed to All Event Subscribers

2. Event Types and Actions

SyncEvent Model

public class SyncEvent : EventArgs

{

public int TenantId { get; set; }

public int SiteId { get; set; }

public string EntityName { get; set; }

public int EntityId { get; set; }

public string Action { get; set; }

public DateTime ModifiedOn { get; set; }

}

Available Actions

public class SyncEventActions

{

public const string Refresh = "Refresh";

public const string Reload = "Reload";

public const string Create = "Create";

public const string Update = "Update";

public const string Delete = "Delete";

}

Common Entity Names

public class EntityNames

{

public const string User = "User";

public const string Site = "Site";

public const string Page = "Page";

public const string Module = "Module";

public const string File = "File";

public const string Folder = "Folder";

public const string Notification = "Notification";

}

3. Creating Event Subscribers

To handle events, implement IEventSubscriber and filter for the entities and actions you care about.

Subscribers are automatically discovered by Oqtane and injected with dependencies.

public class UserActivityEventSubscriber : IEventSubscriber

{

private readonly ILogger<UserActivityEventSubscriber> _logger;

public UserActivityEventSubscriber(ILogger<UserActivityEventSubscriber> logger)

{

_logger = logger;

}

public void EntityChanged(SyncEvent syncEvent)

{

if (syncEvent.EntityName != EntityNames.User)

return;

switch (syncEvent.Action)

{

case SyncEventActions.Create:

_logger.LogInformation("User created: {UserId}", syncEvent.EntityId);

break;

case "Login":

_logger.LogInformation("User logged in: {UserId}", syncEvent.EntityId);

break;

}

}

}

4. User Authentication Events

Login, logout, and registration trigger SyncEvent notifications that you can capture to send notifications,

track user activity, or integrate with external systems.

public class LoginActivityTracker : IEventSubscriber

{

private readonly ILogger<LoginActivityTracker> _logger;

public LoginActivityTracker(ILogger<LoginActivityTracker> logger)

{

_logger = logger;

}

public void EntityChanged(SyncEvent syncEvent)

{

if (syncEvent.EntityName == EntityNames.User && syncEvent.Action == "Login")

{

_logger.LogInformation("User {UserId} logged in at {Time}", syncEvent.EntityId, syncEvent.ModifiedOn);

}

}

}

5. System Entity Events

Besides user events, you can track changes in entities like Pages, Files, and Modules.

public class PageAuditTracker : IEventSubscriber

{

private readonly ILogger<PageAuditTracker> _logger;

public PageAuditTracker(ILogger<PageAuditTracker> logger)

{

_logger = logger;

}

public void EntityChanged(SyncEvent syncEvent)

{

if (syncEvent.EntityName == EntityNames.Page && syncEvent.Action == SyncEventActions.Create)

{

_logger.LogInformation("Page created: {PageId}", syncEvent.EntityId);

}

}

}

6. Custom Module Events

You can create custom events in your own modules using ISyncManager.

public class BlogManager

{

private readonly ISyncManager _syncManager;

public BlogManager(ISyncManager syncManager)

{

_syncManager = syncManager;

}

public void PublishBlog(int blogId)

{

_syncManager.AddSyncEvent(

new Alias { TenantId = 1, SiteId = 1 },

"Blog",

blogId,

"Published"

);

}

}

7. Best Practices

- Filter early — Always check the entity and action before processing.

- Handle exceptions — Never throw unhandled exceptions inside

EntityChanged.

- Log properly — Use structured logging with context placeholders.

- Keep it simple — Extract complex logic to testable services.

public void EntityChanged(SyncEvent syncEvent)

{

try

{

if (syncEvent.EntityName == EntityNames.User && syncEvent.Action == "Login")

{

_logger.LogInformation("User {UserId} logged in", syncEvent.EntityId);

}

}

catch (Exception ex)

{

_logger.LogError(ex, "Error processing event {Action}", syncEvent.Action);

}

}

8. Summary

Oqtane’s event system provides a clean, decoupled way to respond to system changes.

It’s perfect for audit logs, notifications, custom workflows, and integrations.

- Automatic discovery of subscribers

- Centralized event distribution

- Supports custom and system events

- Integrates naturally with dependency injection