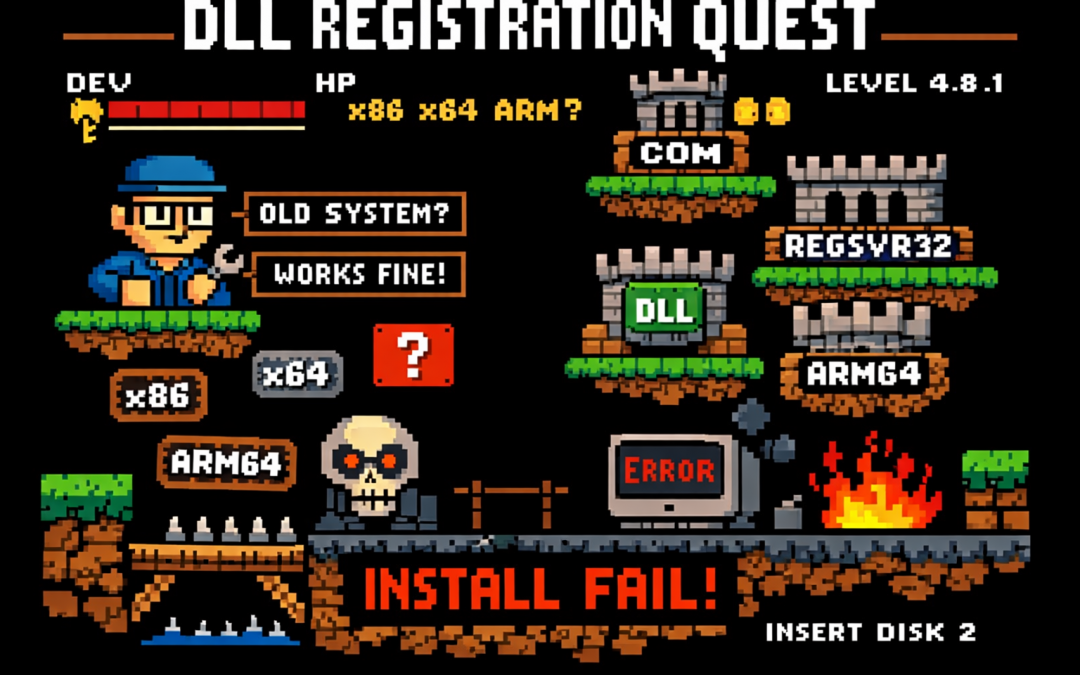

If you’ve ever worked on a traditional .NET Framework application — the kind that predates .NET Core and .NET 5+ — this story may feel painfully familiar.

I’m talking about classic .NET Framework 4.x applications (4.0, 4.5, 4.5.1, 4.5.2, 4.6, 4.6.1, 4.6.2, 4.7, 4.7.1, 4.7.2, 4.8, and the final release 4.8.1). These systems often live long, productive lives… and accumulate interesting technical debt along the way.

This particular system is written in C# and relies heavily on COM components to render video, audio, and PDF content. Under the hood, many of these components are based on technologies like DirectShow filters, ActiveX controls, or other native COM DLLs.

And that’s where the story begins.

The Setup: COM, DirectShow, and Registration

Unlike managed .NET assemblies, COM components don’t just live quietly next to your executable. They need to be registered in the system registry so Windows knows:

- What CLSID they expose

- Which DLL implements that CLSID

- Whether it’s 32-bit or 64-bit

- How it should be activated

For DirectShow-based components (very common for video/audio playback in legacy apps), registration is usually done manually during development using regsvr32.

Example:

regsvr32 MyVideoFilter.dllTo unregister:

regsvr32 /u MyVideoFilter.dllImportant detail that bites a lot of people:

- 32-bit DLLs must be registered using:

C:\Windows\SysWOW64\regsvr32.exe My32BitFilter.dll- 64-bit DLLs must be registered using:

C:\Windows\System32\regsvr32.exe My64BitFilter.dllYes — the folder names are historically confusing.

Development Works… Until It Doesn’t

So here’s the usual development flow:

- You register all required COM DLLs on your development machine

- Visual Studio runs the app

- Video plays, audio works, PDFs render

- Everyone is happy

Then comes the next step.

“Let’s build an installer.”

The Installer Paradox

This is where the real battle story begins.

Your application installer (MSI, InstallShield, WiX, Inno Setup — pick your poison) now needs to:

- Copy the COM DLLs

- Register them during installation

- Unregister them during uninstall

This seems reasonable… until you test it.

The Loop From Hell

Here’s what happens in practice:

- You install your app for testing

- The installer registers its own copies of the COM DLLs

- Your development environment was using different copies (maybe newer, maybe local builds)

- Suddenly:

- Your source build stops working

- Visual Studio debugging breaks

- Another app on your machine mysteriously fails

Then you:

- Uninstall the app

- The installer unregisters the DLLs

- Now nothing works anymore

So you re-register the DLLs manually for development…

…and the cycle repeats.

The Battle Story: It Only Worked… Until It Didn’t

For a long time, this system appeared to work just fine.

Video played. Audio rendered. PDFs opened. No obvious errors.

What we didn’t realize at first was a dangerous hidden assumption:

The system only worked on machines where a previous version had already been installed.

Those older installations had left COM DLLs registered in the system — quietly, globally, and invisibly.

So when we deployed a new version without removing the old one:

- Everything looked fine

- No one suspected missing registrations

- The system passed casual testing

The illusion broke the moment we tried a clean installation.

On a fresh machine — no previous version, no leftover registry entries — the application suddenly failed:

- Components didn’t initialize

- Media rendering silently broke

- COM activation errors appeared only in Event Viewer

The installer claimed it was registering the DLLs.

In reality, it wasn’t doing it correctly — or at least not in the way the application actually needed.

That’s when we realized we were standing on years of accidental state.

Why This Happens

The core problem is simple but brutal:

COM registration is global and mutable.

There is:

- One registry

- One CLSID mapping

- One “active” DLL per COM component

Your development environment, your installed application, and your installer are all fighting over the same global state.

.NET Framework itself isn’t the villain here — it’s just sitting on top of an old Windows integration model that predates modern isolation concepts.

A New Player Enters: ARM64

Just when we thought the problem space was limited to x86 vs x64, another variable entered the scene.

One of the development machines was ARM64.

Modern Windows on ARM adds a new layer of complexity:

- ARM64 native processes

- x64 emulation

- x86 emulation on top of ARM64

From the outside, everything looks like it’s running on x64.

Under the hood, it’s not that simple.

Why This Makes COM Registration Worse

COM registration is architecture-specific:

- x86 DLLs register under one view of the registry

- x64 DLLs register under another

- ARM64 introduces yet another execution context

On Windows ARM:

System32contains ARM64 binariesSysWOW64contains x86 binaries- x64 binaries often run through emulation layers

So now the questions multiply:

- Which

regsvr32did the installer call? - Was it ARM64, x64, or x86?

- Did the app run natively, or under emulation?

- Did the COM DLL match the process architecture?

The result is a system where:

- Some things work on Intel machines

- Some things work on ARM machines

- Some things only work if another version was installed first

At this point, debugging stops being logical and starts being archaeological.

Why This Is So Common in .NET Framework 4.x Apps

Many enterprise and media-heavy applications built on:

- .NET Framework 4.0–4.8.1

- WinForms or WPF

- DirectShow or ActiveX components

were designed in an era where:

- Global COM registration was normal

- Side-by-side isolation was rare

- “Just register the DLL” was accepted practice

These systems work, but they’re fragile — especially on developer machines.

Where the Article Is Going Next

In the rest of this article series, we’ll look at:

- Why install-time registration is often a mistake

- How to isolate development vs runtime environments

- Techniques like:

- Dedicated dev VMs

- Registration-free COM (where possible)

- App-local COM deployment

- Clear ownership rules for installers

- How to survive (and maintain) legacy .NET Framework systems without losing your sanity

If you’ve ever broken your own development environment just by testing your installer — you’re not alone.

This is the cost of living at the intersection of managed code and unmanaged history.