by Joche Ojeda | Jan 5, 2026 | A.I, Postgres

RAG with PostgreSQL and C#

Happy New Year 2026 — let the year begin

Happy New Year 2026 🎉

Let’s start the year with something honest.

This article exists because something broke.

I wasn’t trying to build a demo.

I was building an activity stream — the kind of thing every social or collaborative system eventually needs.

Posts.

Comments.

Reactions.

Short messages.

Long messages.

Noise.

At some point, the obvious question appeared:

“Can I do RAG over this?”

That question turned into this article.

The Original Problem: RAG over an Activity Stream

An activity stream looks simple until you actually use it as input.

In my case:

- The UI language was English

- The content language was… everything else

Users were writing:

- Spanish

- Russian

- Italian

- English

- Sometimes all of them in the same message

Perfectly normal for humans.

Absolutely brutal for naïve RAG.

I tried the obvious approach:

- embed everything

- store vectors

- retrieve similar content

- augment the prompt

And very quickly, RAG went crazy.

Why It Failed (And Why This Matters)

The failure wasn’t dramatic.

No exceptions.

No errors.

Just… wrong answers.

Confident answers.

Fluent answers.

Wrong answers.

The problem was subtle:

- Same concept, different languages

- Mixed-language sentences

- Short, informal activity messages

- No guarantee of language consistency

In an activity stream:

- You don’t control the language

- You don’t control the structure

- You don’t even control what a “document” is

And RAG assumes you do.

That’s when I stopped and realized:

RAG is not “plug-and-play” once your data becomes messy.

So… What Is RAG Really?

RAG stands for Retrieval-Augmented Generation.

The idea is simple:

Retrieve relevant data first, then let the model reason over it.

Instead of asking the model to remember everything, you let it look things up.

Search first.

Generate second.

Sounds obvious.

Still easy to get wrong.

The Real RAG Pipeline (No Marketing)

A real RAG system looks like this:

- Your data lives in a database

- Text is split into chunks

- Each chunk becomes an embedding

- Embeddings are stored as vectors

- A user asks a question

- The question is embedded

- The closest vectors are retrieved

- Retrieved content is injected into the prompt

- The model answers

Every step can fail silently.

Tokenization & Chunking (The First Trap)

Models don’t read text.

They read tokens.

This matters because:

- prompts have hard limits

- activity streams are noisy

- short messages lose context fast

You usually don’t tokenize manually, but you do choose:

- chunk size

- overlap

- grouping strategy

In activity streams, chunking is already a compromise — and multilingual content makes it worse.

Embeddings in .NET (Microsoft.Extensions.AI)

In .NET, embeddings are generated using Microsoft.Extensions.AI.

The important abstraction is:

IEmbeddingGenerator<TInput, TEmbedding>

This keeps your architecture:

- provider-agnostic

- DI-friendly

- survivable over time

Minimal Setup

dotnet add package Microsoft.Extensions.AI

dotnet add package Microsoft.Extensions.AI.OpenAI

Creating an Embedding Generator

using OpenAI;

using Microsoft.Extensions.AI;

using Microsoft.Extensions.AI.OpenAI;

var client = new OpenAIClient("YOUR_API_KEY");

IEmbeddingGenerator<string, Embedding<float>> embeddings =

client.AsEmbeddingGenerator("text-embedding-3-small");

Generating a Vector

var result = await embeddings.GenerateAsync(

new[] { "Some activity text" });

float[] vector = result.First().Vector.ToArray();

That vector is what drives everything that follows.

⚠️ Embeddings Are Model-Locked (And Language Makes It Worse)

Embeddings are model-locked.

Meaning:

Vectors from different embedding models cannot be compared.

Even if:

- the dimension matches

- the text is identical

- the provider is the same

Each model defines its own universe.

But here’s the kicker I learned the hard way:

Multilingual content amplifies this problem.

Even with multilingual-capable models:

- language mixing shifts vector space

- short messages lose semantic anchors

- similarity becomes noisy

In an activity stream:

- English UI

- Spanish content

- Russian replies

- Emoji everywhere

Vector distance starts to mean “kind of related, maybe”.

That’s not good enough.

PostgreSQL + pgvector (Still the Right Choice)

Despite all that, PostgreSQL with pgvector is still the right foundation.

Enable pgvector

CREATE EXTENSION IF NOT EXISTS vector;

Chunk-Based Table

CREATE TABLE doc_chunks (

id bigserial PRIMARY KEY,

document_id bigint NOT NULL,

chunk_index int NOT NULL,

content text NOT NULL,

embedding vector(1536) NOT NULL,

created_at timestamptz NOT NULL DEFAULT now()

);

Technically correct.

Architecturally incomplete — as I later discovered.

Retrieval: Where Things Quietly Go Wrong

SELECT content

FROM doc_chunks

ORDER BY embedding <=> @query_embedding

LIMIT 5;

This query decides:

- what the model sees

- what it ignores

- how wrong the answer will be

When language is mixed, retrieval looks correct — but isn’t.

Classic example: Moscow

So for a Spanish speaker, “Mosca” looks like it should mean insect (which it does), but it’s also the Italian name for Moscow.

Why RAG Failed in This Scenario

Let’s be honest:

- Similar ≠ relevant

- Multilingual ≠ multilingual-safe

- Short activity messages ≠ documents

- Noise ≠ knowledge

RAG didn’t fail because the model was bad.

It failed because the data had no structure.

Why This Article Exists

This article exists because:

- I tried RAG on a real system

- With real users

- Writing in real languages

- In real combinations

And the naïve RAG approach didn’t survive.

What Comes Next

The next article will not be about:

It will be about structured RAG.

How I fixed this by:

- introducing structure into the activity stream

- separating concerns in the pipeline

- controlling language before retrieval

- reducing semantic noise

- making RAG predictable again

In other words:

How to make RAG work after it breaks.

Final Thought

RAG is not magic.

It’s:

search + structure + discipline

If your data is chaotic, RAG will faithfully reflect that chaos — just with confidence.

Happy New Year 2026 🎆

If you’re reading this:

Happy New Year 2026.

Let’s make this the year we stop trusting demos

and start trusting systems that survived reality.

Let the year begin 🚀

by Joche Ojeda | Oct 21, 2024 | A.I, Semantic Kernel

A few weeks ago, I received the exciting news that DevExpress had released a new chat component (you can read more about it here). This was a big deal for me because I had been experimenting with the Semantic Kernel for almost a year. Most of my experiments fell into three categories:

- NUnit projects with no UI (useful when you need to prove a concept).

- XAF ASP.NET projects using a large textbox (String with unlimited size in XAF) to emulate a chat control.

- XAF applications using a custom chat component that I developed—which, honestly, didn’t look great because I’m more of a backend developer than a UI specialist. Still, the component did the job.

Once I got my hands on the new Chat component, the first thing I did was write a property editor to easily integrate it into XAF. You can read more about property editors in XAF here.

With the Chat component property editor in place, I had the necessary tool to accelerate my experiments with the Semantic Kernel (learn more about the Semantic Kernel here).

The Current Experiment

A few weeks ago, I wrote an implementation of the Semantic Kernel Memory Store using DevExpress’s XPO as the data storage solution. You can read about that implementation here. The next step was to integrate this Semantic Memory Store into XAF, and that’s now done. Details about that process can be found here.

What We Have So Far

- A Chat component property editor for XAF.

- A Semantic Kernel Memory Store for XPO that’s compatible with XAF.

With these two pieces, we can create an interesting prototype. The goals for this experiment are:

- Saving “memories” into a domain object (via XPO).

- Querying these memories through the Chat component property editor, using Semantic Kernel chat completions (compatible with all OpenAI APIs).

Step 1: Memory Collection Object

The first thing we need is an object that represents a collection of memories. Here’s the implementation:

[DefaultClassOptions]

public class MemoryChat : BaseObject

{

public MemoryChat(Session session) : base(session) {}

public override void AfterConstruction()

{

base.AfterConstruction();

this.MinimumRelevanceScore = 0.20;

}

double minimumRelevanceScore;

string name;

[Size(SizeAttribute.DefaultStringMappingFieldSize)]

public string Name

{

get => name;

set => SetPropertyValue(nameof(Name), ref name, value);

}

public double MinimumRelevanceScore

{

get => minimumRelevanceScore;

set => SetPropertyValue(nameof(MinimumRelevanceScore), ref minimumRelevanceScore, value);

}

[Association("MemoryChat-MemoryEntries")]

public XPCollection<MemoryEntry> MemoryEntries

{

get => GetCollection<MemoryEntry>(nameof(MemoryEntries));

}

}

This is a simple object. The two main properties are the MinimumRelevanceScore, which is used for similarity searches with embeddings, and the collection of MemoryEntries, where different memories are stored.

Step 2: Adding Memories

The next task is to easily append memories to that collection. I decided to use a non-persistent object displayed in a popup view with a large text area. When the user confirms the action in the dialog, the text gets vectorized and stored as a memory in the collection. You can see the implementation of the view controller here.

Let me highlight the important parts.

When we create the view for the popup window:

private void AppendMemory_CustomizePopupWindowParams(object sender, CustomizePopupWindowParamsEventArgs e)

{

var os = this.Application.CreateObjectSpace(typeof(TextMemory));

var textMemory = os.CreateObject<TextMemory>();

e.View = this.Application.CreateDetailView(os, textMemory);

}

The goal is to show a large textbox where the user can type any text. When they confirm, the text is vectorized and stored as a memory.

Next, storing the memory:

private async void AppendMemory_Execute(object sender, PopupWindowShowActionExecuteEventArgs e)

{

var textMemory = e.PopupWindowViewSelectedObjects[0] as TextMemory;

var currentMemoryChat = e.SelectedObjects[0] as MemoryChat;

var store = XpoMemoryStore.ConnectAsync(xafEntryManager).GetAwaiter().GetResult();

var semanticTextMemory = GetSemanticTextMemory(store);

await semanticTextMemory.SaveInformationAsync(currentMemoryChat.Name, id: Guid.NewGuid().ToString(), text: textMemory.Content);

}

Here, the GetSemanticTextMemory method plays a key role:

private static SemanticTextMemory GetSemanticTextMemory(XpoMemoryStore store)

{

var embeddingModelId = "text-embedding-3-small";

var getKey = () => Environment.GetEnvironmentVariable("OpenAiTestKey", EnvironmentVariableTarget.Machine);

var kernel = Kernel.CreateBuilder()

.AddOpenAIChatCompletion(ChatModelId, getKey.Invoke())

.AddOpenAITextEmbeddingGeneration(embeddingModelId, getKey.Invoke())

.Build();

var embeddingGenerator = new OpenAITextEmbeddingGenerationService(embeddingModelId, getKey.Invoke());

return new SemanticTextMemory(store, embeddingGenerator);

}

This method sets up an embedding generator used to create semantic memories.

Step 3: Querying Memories

To query the stored memories, I created a non-persistent type that interacts with the chat component:

public interface IMemoryData

{

IChatCompletionService ChatCompletionService { get; set; }

SemanticTextMemory SemanticTextMemory { get; set; }

string CollectionName { get; set; }

string Prompt { get; set; }

double MinimumRelevanceScore { get; set; }

}

This interface provides the necessary services to interact with the chat component, including ChatCompletionService and SemanticTextMemory.

Step 4: Handling Messages

Lastly, we handle message-sent callbacks, as explained in this article:

async Task MessageSent(MessageSentEventArgs args)

{

ChatHistory.AddUserMessage(args.Content);

var answers = Value.SemanticTextMemory.SearchAsync(

collection: Value.CollectionName,

query: args.Content,

limit: 1,

minRelevanceScore: Value.MinimumRelevanceScore,

withEmbeddings: true

);

string answerValue = "No answer";

await foreach (var answer in answers)

{

answerValue = answer.Metadata.Text;

}

string messageContent = answerValue == "No answer"

? "There are no memories containing the requested information."

: await Value.ChatCompletionService.GetChatMessageContentAsync($"You are an assistant queried for information. Use this data: {answerValue} to answer the question: {args.Content}.");

ChatHistory.AddAssistantMessage(messageContent);

args.SendMessage(new Message(MessageRole.Assistant, messageContent));

}

Here, we intercept the message, query the SemanticTextMemory, and use the results to generate an answer with the chat completion service.

This was a long post, but I hope it’s useful for you all. Until next time—XAF OUT!

You can find the full implementation on this repo

by Joche Ojeda | Oct 15, 2024 | A.I, Semantic Kernel, XAF, XPO

A few weeks ago, I forked the Semantic Kernel repository to experiment with it. One of my first experiments was to create a memory provider for XPO. The task was not too difficult; basically, I needed to implement the IMemoryStore interface, add some XPO boilerplate code, and just like that, we extended the Semantic Kernel memory store to support 10+ databases. You can check out the code for the XpoMemoryStore here.

My initial goal in creating the XpoMemoryStore was simply to see if XPO would be a good fit for handling embeddings. Spoiler alert: it was! To understand the basic functionality of the plugin, you can take a look at the integration test here.

As you can see, usage is straightforward. You start by connecting to the database that handles embedding collections, and all you need is a valid XPO connection string:

using XpoMemoryStore db = await XpoMemoryStore.ConnectAsync("XPO connection string");

In my original design, everything worked fine, but I faced some challenges when trying to use my new XpoMemoryStore in XAF. Here’s what I encountered:

- The implementation of XpoMemoryStore uses its own data layer, which can lead to issues. This needs to be rewritten to use the same data layer as XAF.

- The XpoEntry implementation cannot be extended. In some use cases, you might want to use a different object to store the embeddings, perhaps one that has an association with another object.

To address these problems, I introduced the IXpoEntryManager interface. The goal of this interface is to handle object creation and queries.

public interface IXpoEntryManager

{

T CreateObject();

public event EventHandler ObjectCreatedEvent;

void Commit();

IQueryable GetQuery(bool inTransaction = true);

void Delete(object instance);

void Dispose();

}

Now, object creation is handled through the CreateObject<T> method, allowing the underlying implementation to be changed to use a UnitOfWork or ObjectSpace. There’s also the ObjectCreatedEvent event, which lets you access the newly created object in case you need to associate it with another object. Lastly, the GetQuery<T> method enables redirecting the search for records to a different type.

I’ll keep updating the code as needed. If you’d like to discuss AI, XAF, or .NET, feel free to schedule a meeting: Schedule a Meeting with us.

Until next time, XAF out!

Related Article

https://www.jocheojeda.com/2024/09/04/using-the-imemorystore-interface-and-devexpress-xpo-orm-to-implement-a-custom-memory-store-for-semantic-kernel/

by Joche Ojeda | Dec 31, 2023 | A.I

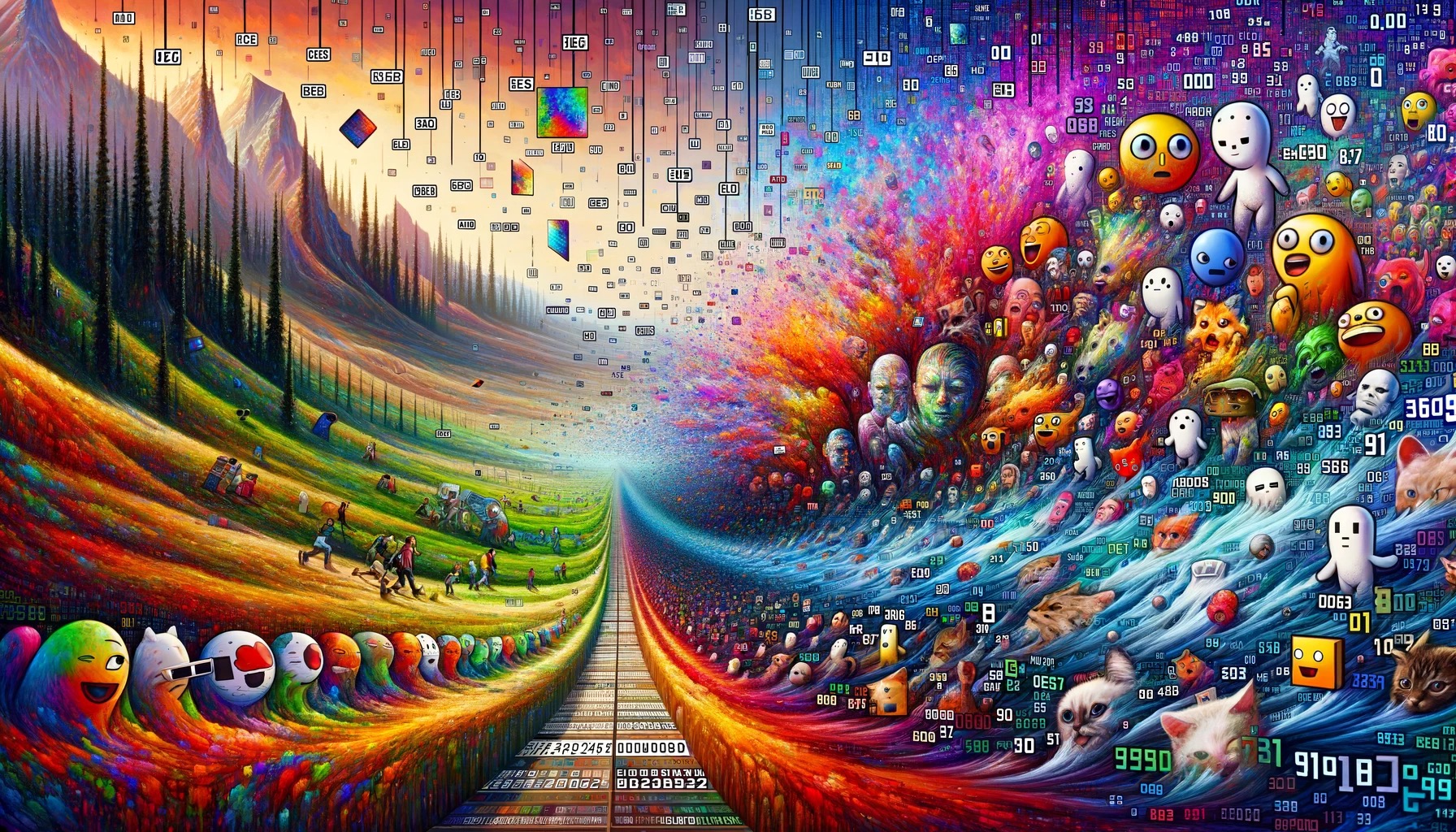

Unpacking Memes and AI Embeddings: An Intriguing Intersection

The Essence of Embeddings in AI

In the realm of artificial intelligence, the concept of an embedding is pivotal. It’s a method of converting complex, high-dimensional data like text, images, or sounds into a lower-dimensional space. This transformation captures the essence of the data’s most relevant features.

Imagine a vast library of books. An embedding is like a skilled librarian who can distill each book into a single, insightful summary. This process enables machines to process and understand vast swathes of data more efficiently and meaningfully.

The Meme: A Cultural Embedding

A meme is a cultural artifact, often an image with text, that encapsulates a collective experience, emotion, or idea in a highly condensed format. It’s a snippet of culture, distilled down to its most essential and relatable elements.

The Intersection: AI Embeddings and Memes

The connection between AI embeddings and memes lies in their shared essence of abstraction and distillation. Both serve as compact representations of more complex entities. An AI embedding abstracts media into a form that captures its most relevant features, just as a meme condenses an experience or idea into a simple format.

Implications and Insights

This intersection offers fascinating implications. For instance, when AI learns to understand and generate memes, it’s tapping into the cultural and emotional undercurrents that memes represent. This requires a nuanced understanding of human experiences and societal contexts – a significant challenge for AI.

Moreover, the study of memes can inform AI research, leading to more adaptable and resilient AI models.

Conclusion

In conclusion, while AI embeddings and memes operate in different domains, they share a fundamental similarity in their approach to abstraction. This intersection opens up possibilities for both AI development and our understanding of cultural phenomena.

by Joche Ojeda | Dec 17, 2023 | A.I

In the world of machine learning (ML) and artificial intelligence (AI), “embeddings” refer to dense, low-dimensional, yet informative representations of high-dimensional data.

These representations are used to capture the essence of the data in a form that is more manageable for various ML tasks. Here’s a more detailed explanation:

What are Embeddings?

Definition: Embeddings are a way to transform high-dimensional data (like text, images, or sound) into a lower-dimensional space. This transformation aims to preserve relevant properties of the original data, such as semantic or contextual relationships.

Purpose: They are especially useful in natural language processing (NLP), where words, sentences, or even entire documents are converted into vectors in a continuous vector space. This enables the ML models to understand and process textual data more effectively, capturing nuances like similarity, context, and even analogies.

Creating Embeddings

Word Embeddings: For text, embeddings are typically created using models like Word2Vec, GloVe, or FastText. These models are trained on large text corpora and learn to represent words as vectors in a way that captures their semantic meaning.

Image and Audio Embeddings: For images and audio, embeddings are usually generated using deep learning models like convolutional neural networks (CNNs). These networks learn to encode the visual or auditory features of the input into a compact vector.

Training Process: Training an embedding model involves feeding it a large amount of data so that it learns a dense representation of the inputs. The model adjusts its parameters to minimize the difference between the embeddings of similar items and maximize the difference between embeddings of dissimilar items.

Differences in Embeddings Across Models

Dimensionality and Structure: Different models produce embeddings of different sizes and structures. For instance, Word2Vec might produce 300-dimensional vectors, while a CNN for image processing might output a 2048-dimensional vector.

Captured Information: The information captured in embeddings varies based on the model and training data. For example, text embeddings might capture semantic meaning, while image embeddings capture visual features.

Model-Specific Characteristics: Each embedding model has its unique way of understanding and encoding information. For instance, BERT (a language model) generates context-dependent embeddings, meaning the same word can have different embeddings based on its context in a sentence.

Transfer Learning and Fine-tuning: Pre-trained embeddings can be used in various tasks as a starting point (transfer learning). These embeddings can also be fine-tuned on specific tasks to better suit the needs of a particular application.

Conclusion

In summary, embeddings are a fundamental concept in ML and AI, enabling models to work efficiently with complex and high-dimensional data. The specific characteristics of embeddings vary based on the model used, the data it was trained on, and the task at hand. Understanding and creating embeddings is a crucial skill in AI, as it directly impacts the performance and capabilities of the models.