by Joche Ojeda | Jan 8, 2026 | C#, XAF

Async/await in C# is often described as “non-blocking,” but that description hides an important detail:

await is not just about waiting — it is about where execution continues afterward.

Understanding that single idea explains:

- why deadlocks happen,

- why

ConfigureAwait(false) exists,

- and why it *reduces* damage without fixing the root cause.

This article is not just theory. It’s written because this exact class of problem showed up again in real production code during the first week of 2026 — and it took a context-level fix to resolve it.

The Hidden Mechanism: Context Capture

When you await a task, C# does two things:

- It pauses the current method until the awaited task completes.

- It captures the current execution context (if one exists) so the continuation can resume there.

That context might be:

- a UI thread (WPF, WinForms, MAUI),

- a request context (classic ASP.NET),

- or no special context at all (ASP.NET Core, console apps).

This default behavior is intentional. It allows code like this to work safely:

var data = await LoadAsync();

MyLabel.Text = data.Name; // UI-safe continuation

But that same mechanism becomes dangerous when async code is blocked synchronously.

The Root Problem: Blocking on Async

Deadlocks typically appear when async code is forced into a synchronous shape:

var result = GetDataAsync().Result; // or .Wait()

What happens next:

- The calling thread blocks, waiting for the async method to finish.

- The async method completes its awaited operation.

- The continuation tries to resume on the original context.

- That context is blocked.

- Nothing can proceed.

💥 Deadlock.

This is not an async bug. This is a context dependency cycle.

The Blast Radius Concept

Blocking on async is the explosion.

The blast radius is how much of the system is taken down with it.

Full blast (default await)

- Continuation *requires* the blocked context

- The async operation cannot complete

- The caller never unblocks

- Everything stops

Reduced blast (ConfigureAwait(false))

- Continuation does not require the original context

- It resumes on a thread pool thread

- The async operation completes

- The blocking call unblocks

The original mistake still exists — but the damage is contained.

The real fix is “don’t block on async,”

but ConfigureAwait(false) reduces the blast radius when someone does.

What ConfigureAwait(false) Actually Does

await SomeAsyncOperation().ConfigureAwait(false);

This tells the runtime:

“I don’t need to resume on the captured context. Continue wherever it’s safe to do so.”

Important clarifications:

- It does not make code faster by default

- It does not make code parallel

- It does not remove the need for proper async flow

- It only removes context dependency

Why This Matters in Real Code

Async code rarely exists in isolation.

A method often awaits another method, which awaits another:

await AAsync();

await BAsync();

await CAsync();

If any method in that chain requires a specific context, the entire chain becomes context-bound.

That is why:

- library code must be careful,

- deep infrastructure layers must avoid context assumptions,

- and UI layers must be explicit about where context is required.

When ConfigureAwait(false) Is the Right Tool

Use it when all of the following are true:

- The method does not interact with UI state

- The method does not depend on a request context

- The method is infrastructure, library, or backend logic

- The continuation does not care which thread resumes it

This is especially true for:

- NuGet packages

- shared libraries

- data access layers

- network and IO pipelines

What It Is Not

ConfigureAwait(false) is not:

- a fix for bad async usage

- a substitute for proper async flow

- a reason to block on tasks

- something to blindly apply everywhere

It is a damage-control tool, not a cure.

A Real Incident: When None of the Usual Fixes Worked

First week of 2026.

The first task I had with the programmers in my office was to investigate a problem in a trading block. The symptoms looked like a classic async issue: timing bugs, inconsistent behavior, and freezes that felt “await-shaped.”

We did what experienced .NET teams typically do when async gets weird:

- Reviewed the full async/await chain end-to-end

- Double-checked the source code carefully (everything looked fine)

- Tried the usual “tools people reach for” under pressure:

.Wait().GetAwaiter().GetResult()- wrapping in

Task.Run(...)

- adding

ConfigureAwait(false)

- mixing combinations of those approaches

None of it reliably fixed the problem.

At that point it stopped being a “missing await” story. It became a “the model is right but reality disagrees” story.

One of the programmers, Daniel, and I went deeper. I found myself mentally replaying every async pattern I know — especially because I’ve written async-heavy code myself, including library work like SyncFramework, where I synchronize databases and deal with long-running operations.

That’s the moment where this mental model matters: it forces you to stop treating await like syntax and start treating it like mechanics.

The Actual Root Cause: It Was the Context

In the end, the culprit wasn’t which pattern we used — it was where the continuation was allowed to run.

This application was built on DevExpress XAF. In this environment, the “correct” continuation behavior is often tied to XAF’s own scheduling and application lifecycle rules. XAF provides a mechanism to run code in its synchronization context — for example using BlazorApplication.InvokeAsync, which ensures that continuations run where the framework expects.

Once we executed the problematic pipeline through XAF’s synchronization context, the issue was solved.

No clever pattern. No magical await. No extra parallelism.

Just: the right context.

And this is not unique to XAF. Similar ideas exist in:

- Windows Forms (UI thread affinity + SynchronizationContext)

- WPF (Dispatcher context)

- Any framework that requires work to resume on a specific thread/context

Why I’m Writing This

What I wanted from this experience is simple: don’t forget it.

Because what makes this kind of incident dangerous is that it looks like a normal async bug — and the internet is full of “four fixes” people cycle through:

- add/restore missing

await

- use

.Wait() / .Result

- wrap in

Task.Run()

- use

ConfigureAwait(false)

Sometimes those are relevant. Sometimes they’re harmful. And sometimes… they’re all beside the point.

In our case, the missing piece was framework context — and once you see that, you realize why the “blast radius” framing is so useful:

- Blocking is the explosion.

ConfigureAwait(false) contains damage when someone blocks.- If a framework requires a specific synchronization context, the fix may be to supply the correct context explicitly.

That’s what happened here. And that’s why I’m capturing it as live knowledge, not just documentation.

The Mental Model to Keep

- Async bugs are often context bugs

- Blocking creates the explosion

- Context capture determines the blast radius

ConfigureAwait(false) limits the damage- Proper async flow prevents the explosion entirely

- Frameworks may require their own synchronization context

- Correct async code can still fail in the wrong context

Async is not just about tasks. It’s about where your code is allowed to continue.

by Joche Ojeda | Oct 16, 2025 | Events, Oqtane

OK, I’m still blocked from GitHub Copilot, so I still have more things to write about.

In this article, the topic that we’re going to see is the event system of Oqtane.For example, usually in most systems you want to hook up something when the application starts.

In XAF from Developer Express, which is my specialty (I mean, that’s the framework I really know well),

you have the DB Updater, which you can use to set up some initial data.

In Oqtane, you have the Module Manager, but there are also other types of events that you might need —

for example, when the user is created or when the user signs in for the first time.

So again, using the method that I explained in my previous article — the “OK, I have a doubt” method —

I basically let the guide of Copilot hike over my installation folder or even the Oqtane source code itself, and try to figure out how to do it.

That’s how I ended up using event subscribers.

In one of my prototypes, what I needed to do was detect when the user is created and then create some records in a different system

using that user’s information. So I’ll show an example of that type of subscriber, and I’ll actually share the

Oqtane Event Handling Guide here, which explains how you can hook up to system events.

I’m sure there are more events available, but this is what I’ve found so far and what I’ve tested.

I guess I’ll make a video about all these articles at some point, but right now, I’m kind of vibing with other systems.

Whenever I get blocked, I write something about my research with Oqtane.

Oqtane Event Handling Guide

Comprehensive guide to capturing and responding to system events in Oqtane

This guide explains how to handle events in Oqtane, particularly focusing on user authentication events (login, logout, creation)

and other system events. Learn to build modules that respond to framework events and create custom event-driven functionality.

Version: 1.0.0

Last Updated: October 3, 2025

Oqtane Version: 6.0+

Framework: .NET 9.0

1. Overview of Oqtane Event System

Oqtane uses a centralized event system based on the SyncManager that broadcasts events throughout the application when entities change.

This enables loose coupling between components and allows modules to respond to framework events without tight integration.

Key Components

- SyncManager — Central event hub that broadcasts entity changes

- SyncEvent — Event data containing entity information and action type

- IEventSubscriber — Interface for objects that want to receive events

- EventDistributorHostedService — Background service that distributes events to subscribers

Entity Changes → SyncManager → EventDistributorHostedService → IEventSubscriber Implementations

↓

SyncEvent Created → Distributed to All Event Subscribers

2. Event Types and Actions

SyncEvent Model

public class SyncEvent : EventArgs

{

public int TenantId { get; set; }

public int SiteId { get; set; }

public string EntityName { get; set; }

public int EntityId { get; set; }

public string Action { get; set; }

public DateTime ModifiedOn { get; set; }

}

Available Actions

public class SyncEventActions

{

public const string Refresh = "Refresh";

public const string Reload = "Reload";

public const string Create = "Create";

public const string Update = "Update";

public const string Delete = "Delete";

}

Common Entity Names

public class EntityNames

{

public const string User = "User";

public const string Site = "Site";

public const string Page = "Page";

public const string Module = "Module";

public const string File = "File";

public const string Folder = "Folder";

public const string Notification = "Notification";

}

3. Creating Event Subscribers

To handle events, implement IEventSubscriber and filter for the entities and actions you care about.

Subscribers are automatically discovered by Oqtane and injected with dependencies.

public class UserActivityEventSubscriber : IEventSubscriber

{

private readonly ILogger<UserActivityEventSubscriber> _logger;

public UserActivityEventSubscriber(ILogger<UserActivityEventSubscriber> logger)

{

_logger = logger;

}

public void EntityChanged(SyncEvent syncEvent)

{

if (syncEvent.EntityName != EntityNames.User)

return;

switch (syncEvent.Action)

{

case SyncEventActions.Create:

_logger.LogInformation("User created: {UserId}", syncEvent.EntityId);

break;

case "Login":

_logger.LogInformation("User logged in: {UserId}", syncEvent.EntityId);

break;

}

}

}

4. User Authentication Events

Login, logout, and registration trigger SyncEvent notifications that you can capture to send notifications,

track user activity, or integrate with external systems.

public class LoginActivityTracker : IEventSubscriber

{

private readonly ILogger<LoginActivityTracker> _logger;

public LoginActivityTracker(ILogger<LoginActivityTracker> logger)

{

_logger = logger;

}

public void EntityChanged(SyncEvent syncEvent)

{

if (syncEvent.EntityName == EntityNames.User && syncEvent.Action == "Login")

{

_logger.LogInformation("User {UserId} logged in at {Time}", syncEvent.EntityId, syncEvent.ModifiedOn);

}

}

}

5. System Entity Events

Besides user events, you can track changes in entities like Pages, Files, and Modules.

public class PageAuditTracker : IEventSubscriber

{

private readonly ILogger<PageAuditTracker> _logger;

public PageAuditTracker(ILogger<PageAuditTracker> logger)

{

_logger = logger;

}

public void EntityChanged(SyncEvent syncEvent)

{

if (syncEvent.EntityName == EntityNames.Page && syncEvent.Action == SyncEventActions.Create)

{

_logger.LogInformation("Page created: {PageId}", syncEvent.EntityId);

}

}

}

6. Custom Module Events

You can create custom events in your own modules using ISyncManager.

public class BlogManager

{

private readonly ISyncManager _syncManager;

public BlogManager(ISyncManager syncManager)

{

_syncManager = syncManager;

}

public void PublishBlog(int blogId)

{

_syncManager.AddSyncEvent(

new Alias { TenantId = 1, SiteId = 1 },

"Blog",

blogId,

"Published"

);

}

}

7. Best Practices

- Filter early — Always check the entity and action before processing.

- Handle exceptions — Never throw unhandled exceptions inside

EntityChanged.

- Log properly — Use structured logging with context placeholders.

- Keep it simple — Extract complex logic to testable services.

public void EntityChanged(SyncEvent syncEvent)

{

try

{

if (syncEvent.EntityName == EntityNames.User && syncEvent.Action == "Login")

{

_logger.LogInformation("User {UserId} logged in", syncEvent.EntityId);

}

}

catch (Exception ex)

{

_logger.LogError(ex, "Error processing event {Action}", syncEvent.Action);

}

}

8. Summary

Oqtane’s event system provides a clean, decoupled way to respond to system changes.

It’s perfect for audit logs, notifications, custom workflows, and integrations.

- Automatic discovery of subscribers

- Centralized event distribution

- Supports custom and system events

- Integrates naturally with dependency injection

by Joche Ojeda | Oct 5, 2025 | Oqtane, ORM

In this article, I’ll show you what to do after you’ve obtained and opened an Oqtane solution. Specifically, we’ll go through two different ways to set up your database for the first time.

- Using the setup wizard — this option appears automatically the first time you run the application.

- Configuring it manually — by directly editing the

appsettings.json file to skip the wizard.

Both methods achieve the same result. The only difference is that, if you configure the database manually, you won’t see the setup wizard during startup.

Step 1: Running the Application for the First Time

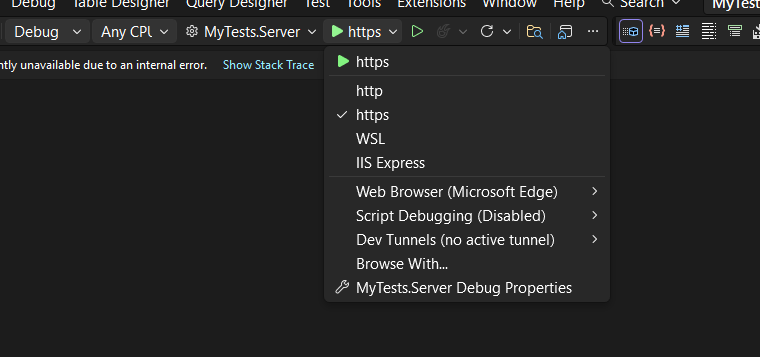

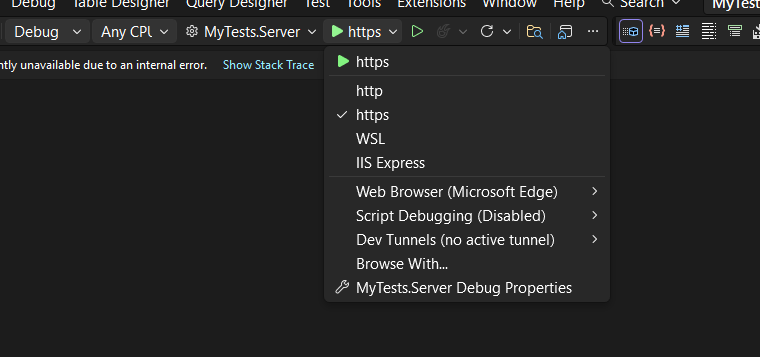

Once your solution is open in Visual Studio, set the Server project as the startup project. Then run it just as you would with any ASP.NET Core application.

You’ll notice several run options — I recommend using the HTTPS version instead of IIS Express (I stopped using IIS Express because it doesn’t work well on ARM-based computers).

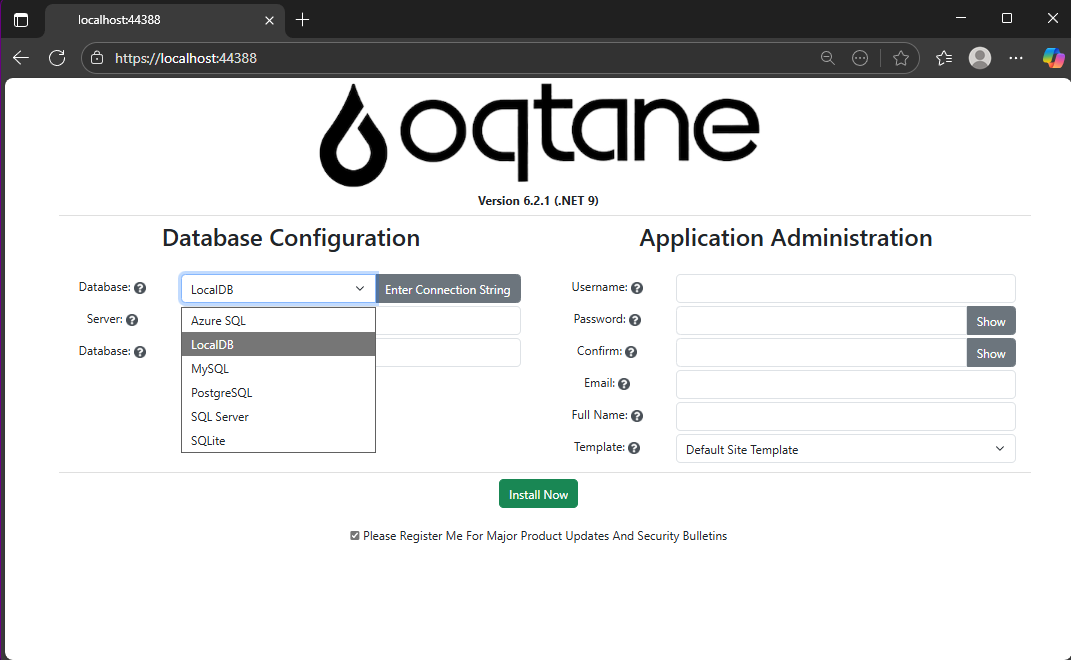

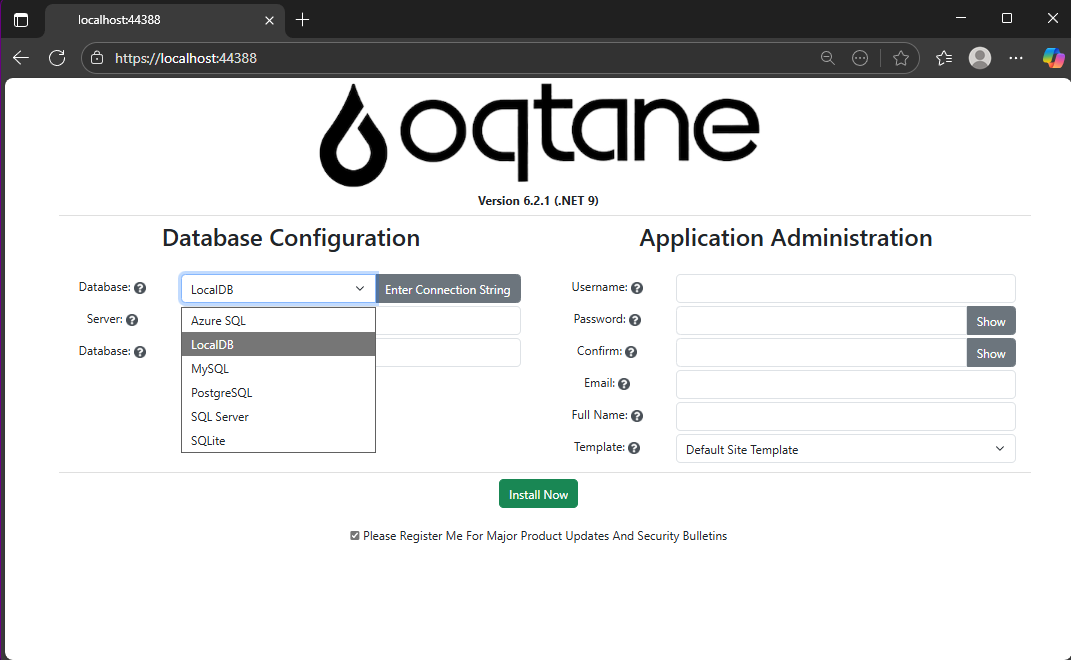

When you run the application for the first time and your settings file is still empty, you’ll see the Database Setup Wizard. As shown in the image, the wizard allows you to select a database provider and configure it through a form.

There’s also an option to paste your connection string directly. Make sure it’s a valid Entity Framework Core connection string.

After that, fill in the admin user’s details — username, email, and password — and you’re done. Once this process completes, you’ll have a working Oqtane installation.

Step 2: Setting Up the Database Manually

If you prefer to skip the wizard, you can configure the database manually. To do this, open the appsettings.json file and add the following parameters:

{

"DefaultDBType": "Oqtane.Database.Sqlite.SqliteDatabase, Oqtane.Server",

"ConnectionStrings": {

"DefaultConnection": "Data Source=Oqtane-202510052045.db;"

},

"Installation": {

"DefaultAlias": "https://localhost:44388",

"HostPassword": "MyPasswor25!",

"HostEmail": "joche@myemail.com",

"SiteTemplate": "",

"DefaultTheme": "",

"DefaultContainer": ""

}

}

Here you need to specify:

- The database provider type (e.g., SQLite, SQL Server, PostgreSQL, etc.)

- The connection string

- The admin email and password for the first user — known as the host user (essentially the root or super admin).

This is the method I usually use now since I’ve set up Oqtane so many times recently that I’ve grown tired of the wizard. However, if you’re new to Oqtane, the wizard is a great way to get started.

Wrapping Up

That’s it for this setup guide! By now, you should have a running Oqtane installation configured either through the setup wizard or manually via the configuration file. Both methods give you a solid foundation to start exploring what Oqtane can do.

In the next article, we’ll dive into the Oqtane backend, exploring how the framework handles modules, data, and the underlying architecture that makes it flexible and powerful. Stay tuned — things are about to get interesting!

by Joche Ojeda | May 5, 2025 | Uncategorized

Integration testing is a critical phase in software development where individual modules are combined and tested as a group. In our accounting system, we’ve created a robust integration test that demonstrates how the Document module and Chart of Accounts module interact to form a functional accounting system. In this post, I’ll explain the components and workflow of our integration test.

The Architecture of Our Integration Test

Our integration test simulates a small retail business’s accounting operations. Let’s break down the key components:

Test Fixture Setup

The AccountingIntegrationTests class contains all our test methods and is decorated with the [TestFixture] attribute to identify it as a NUnit test fixture. The Setup method initializes our services and data structures:

[SetUp]

public async Task Setup()

{

// Initialize services

_auditService = new AuditService();

_documentService = new DocumentService(_auditService);

_transactionService = new TransactionService();

_accountValidator = new AccountValidator();

_accountBalanceCalculator = new AccountBalanceCalculator();

// Initialize storage

_accounts = new Dictionary<string, AccountDto>();

_documents = new Dictionary<string, IDocument>();

_transactions = new Dictionary<string, ITransaction>();

// Create Chart of Accounts

await SetupChartOfAccounts();

}

This method:

- Creates instances of our services

- Sets up in-memory storage for our entities

- Calls

SetupChartOfAccounts() to create our initial chart of accounts

Chart of Accounts Setup

The SetupChartOfAccounts method creates a basic chart of accounts for our retail business:

private async Task SetupChartOfAccounts()

{

// Clear accounts dictionary in case this method is called multiple times

_accounts.Clear();

// Assets (1xxxx)

await CreateAccount("Cash", "10100", AccountType.Asset, "Cash on hand and in banks");

await CreateAccount("Accounts Receivable", "11000", AccountType.Asset, "Amounts owed by customers");

// ... more accounts

// Verify all accounts are valid

foreach (var account in _accounts.Values)

{

bool isValid = _accountValidator.ValidateAccount(account);

Assert.That(isValid, Is.True, $"Account {account.AccountName} validation failed");

}

// Verify expected number of accounts

Assert.That(_accounts.Count, Is.EqualTo(17), "Expected 17 accounts in chart of accounts");

}

This method:

- Creates accounts for each category (Assets, Liabilities, Equity, Revenue, and Expenses)

- Validates each account using our

AccountValidator

- Ensures we have the expected number of accounts

Individual Transaction Tests

We have separate test methods for specific transaction types:

Purchase of Inventory

CanRecordPurchaseOfInventory demonstrates recording a supplier invoice:

[Test]

public async Task CanRecordPurchaseOfInventory()

{

// Arrange - Create document

var document = new DocumentDto { /* properties */ };

// Act - Create document, transaction, and entries

var createdDocument = await _documentService.CreateDocumentAsync(document, TEST_USER);

// ... create transaction and entries

// Validate transaction

var isValid = await _transactionService.ValidateTransactionAsync(

createdTransaction.Id, ledgerEntries);

// Assert

Assert.That(isValid, Is.True, "Transaction should be balanced");

}

This test:

- Creates a document for our inventory purchase

- Creates a transaction linked to that document

- Creates ledger entries (debiting Inventory, crediting Accounts Payable)

- Validates that the transaction is balanced (debits = credits)

Sale to Customer

CanRecordSaleToCustomer demonstrates recording a customer sale:

[Test]

public async Task CanRecordSaleToCustomer()

{

// Similar pattern to inventory purchase, but with sale-specific entries

// ...

// Create ledger entries - a more complex transaction with multiple entries

var ledgerEntries = new List<ILedgerEntry>

{

// Cash received

// Sales revenue

// Cost of goods sold

// Reduce inventory

};

// Validate transaction

// ...

}

This test is more complex, recording both the revenue side (debit Cash, credit Sales Revenue) and the cost side (debit Cost of Goods Sold, credit Inventory) of a sale.

Full Accounting Cycle Test

The CanExecuteFullAccountingCycle method ties everything together:

[Test]

public async Task CanExecuteFullAccountingCycle()

{

// Run these in a defined order, with clean account setup first

_accounts.Clear();

_documents.Clear();

_transactions.Clear();

await SetupChartOfAccounts();

// 1. Record inventory purchase

await RecordPurchaseOfInventory();

// 2. Record sale to customer

await RecordSaleToCustomer();

// 3. Record utility expense

await RecordBusinessExpense();

// 4. Create a payment to supplier

await RecordPaymentToSupplier();

// 5. Verify account balances

await VerifyAccountBalances();

}

This test:

- Starts with a clean state

- Records a sequence of business operations

- Verifies the final account balances

Mock Account Balance Calculator

The MockAccountBalanceCalculator is a crucial part of our test that simulates how a real database would work:

public class MockAccountBalanceCalculator : AccountBalanceCalculator

{

private readonly Dictionary<string, AccountDto> _accounts;

private readonly Dictionary<Guid, List<LedgerEntryDto>> _ledgerEntriesByTransaction = new();

private readonly Dictionary<Guid, decimal> _accountBalances = new();

public MockAccountBalanceCalculator(

Dictionary<string, AccountDto> accounts,

Dictionary<string, ITransaction> transactions)

{

_accounts = accounts;

// Create mock ledger entries for each transaction

InitializeLedgerEntries(transactions);

// Calculate account balances based on ledger entries

CalculateAllBalances();

}

// Methods to initialize and calculate

// ...

}

This class:

- Takes our accounts and transactions as inputs

- Creates a collection of ledger entries for each transaction

- Calculates account balances based on these entries

- Provides methods to query account balances and ledger entries

The InitializeLedgerEntries method creates a collection of ledger entries for each transaction:

private void InitializeLedgerEntries(Dictionary<string, ITransaction> transactions)

{

// For inventory purchase

if (transactions.TryGetValue("InventoryPurchase", out var inventoryPurchase))

{

var entries = new List<LedgerEntryDto>

{

// Create entries for this transaction

// ...

};

_ledgerEntriesByTransaction[inventoryPurchase.Id] = entries;

}

// For other transactions

// ...

}

The CalculateAllBalances method processes these entries to calculate account balances:

private void CalculateAllBalances()

{

// Initialize all account balances to zero

foreach (var account in _accounts.Values)

{

_accountBalances[account.Id] = 0m;

}

// Process each transaction's ledger entries

foreach (var entries in _ledgerEntriesByTransaction.Values)

{

foreach (var entry in entries)

{

if (entry.EntryType == EntryType.Debit)

{

_accountBalances[entry.AccountId] += entry.Amount;

}

else // Credit

{

_accountBalances[entry.AccountId] -= entry.Amount;

}

}

}

}

This approach closely mirrors how a real accounting system would work with a database:

- Ledger entries are stored in collections (similar to database tables)

- Account balances are calculated by processing all relevant entries

- The calculator provides methods to query this data (similar to a repository)

Balance Verification

The VerifyAccountBalances method uses our mock calculator to verify account balances:

private async Task VerifyAccountBalances()

{

// Create mock balance calculator

var mockBalanceCalculator = new MockAccountBalanceCalculator(_accounts, _transactions);

// Verify individual account balances

decimal cashBalance = mockBalanceCalculator.CalculateAccountBalance(

_accounts["Cash"].Id,

_testDate.AddDays(15)

);

Assert.That(cashBalance, Is.EqualTo(-2750m), "Cash balance is incorrect");

// ... verify other account balances

// Also verify the accounting equation

// ...

}

The Benefits of Our Collection-Based Approach

Our redesigned MockAccountBalanceCalculator offers several advantages:

- Data-Driven: All calculations are based on collections of data, not hardcoded values.

- Flexible: New transactions can be added easily without changing calculation logic.

- Maintainable: If transaction amounts change, we only need to update them in one place.

- Realistic: This approach closely mirrors how a real database-backed accounting system would work.

- Extensible: We can add support for more complex queries like filtering by date range.

The Goals of Our Integration Test

Our integration test serves several important purposes:

- Verify Module Integration: Ensures that the Document module and Chart of Accounts module work correctly together.

- Validate Business Workflows: Confirms that standard accounting workflows (purchasing, sales, expenses, payments) function as expected.

- Ensure Data Integrity: Verifies that all transactions maintain balance (debits = credits) and that account balances are accurate.

- Test Double-Entry Accounting: Confirms that our system properly implements double-entry accounting principles where every transaction affects at least two accounts.

- Validate Accounting Equation: Ensures that the fundamental accounting equation (Assets = Liabilities + Equity + (Revenues – Expenses)) remains balanced.

Conclusion

This integration test demonstrates the core functionality of our accounting system using a data-driven approach that closely mimics a real database. By simulating a retail business’s transactions and storing them in collections, we’ve created a realistic test environment for our double-entry accounting system.

The collection-based approach in our MockAccountBalanceCalculator allows us to test complex accounting logic without an actual database, while still ensuring that our calculations are accurate and our accounting principles are sound.

While this test uses in-memory collections rather than a database, it provides a strong foundation for testing the business logic of our accounting system in a way that would translate easily to a real-world implementation.

Repo

egarim/SivarErp: Open Source ERP

About Us

YouTube

https://www.youtube.com/c/JocheOjedaXAFXAMARINC

Our sites

Let’s discuss your XAF

This call/zoom will give you the opportunity to define the roadblocks in your current XAF solution. We can talk about performance, deployment or custom implementations. Together we will review you pain points and leave you with recommendations to get your app back in track

https://calendly.com/bitframeworks/bitframeworks-free-xaf-support-hour

Our free A.I courses on Udemy

by Joche Ojeda | May 5, 2025 | Uncategorized

The chart of accounts module is a critical component of any financial accounting system, serving as the organizational structure that categorizes financial transactions. As a software developer working on accounting applications, understanding how to properly implement a chart of accounts module is essential for creating robust and effective financial management solutions.

What is a Chart of Accounts?

Before diving into the implementation details, let’s clarify what a chart of accounts is. In accounting, the chart of accounts is a structured list of all accounts used by an organization to record financial transactions. These accounts are categorized by type (assets, liabilities, equity, revenue, and expenses) and typically follow a numbering system to facilitate organization and reporting.

Core Components of a Chart of Accounts Module

Based on best practices in financial software development, a well-designed chart of accounts module should include:

1. Account Entity

The fundamental entity in the module is the account itself. A properly designed account entity should include:

- A unique identifier (typically a GUID in modern systems)

- Account name

- Account type (asset, liability, equity, revenue, expense)

- Official account code (often used for regulatory reporting)

- Reference to financial statement lines

- Audit information (who created/modified the account and when)

- Archiving capability (for soft deletion)

2. Account Type Enumeration

Account types are typically implemented as an enumeration:

public enum AccountType

{

Asset = 1,

Liability = 2,

Equity = 3,

Revenue = 4,

Expense = 5

}

This enumeration serves as more than just a label—it determines critical business logic, such as whether an account normally has a debit or credit balance.

3. Account Validation

A robust chart of accounts module includes validation logic for accounts:

- Ensuring account codes follow the required format (typically numeric)

- Verifying that account codes align with their account types (e.g., asset accounts starting with “1”)

- Validating consistency between account types and financial statement lines

- Checking that account names are not empty and are unique

4. Balance Calculation

One of the most important functions of the chart of accounts module is calculating account balances:

- Point-in-time balance calculations (as of a specific date)

- Period turnover calculations (debit and credit movement within a date range)

- Determining if an account has any transactions

Implementation Best Practices

When implementing a chart of accounts module, consider these best practices:

1. Use Interface-Based Design

Implement interfaces like IAccount to define the contract for account entities:

public interface IAccount : IEntity, IAuditable, IArchivable

{

Guid? BalanceAndIncomeLineId { get; set; }

string AccountName { get; set; }

AccountType AccountType { get; set; }

string OfficialCode { get; set; }

}

2. Apply SOLID Principles

- Single Responsibility: Separate account validation, balance calculation, and persistence

- Open-Closed: Design for extension without modification (e.g., for custom account types)

- Liskov Substitution: Ensure derived implementations can substitute base interfaces

- Interface Segregation: Create focused interfaces for different concerns

- Dependency Inversion: Depend on abstractions rather than concrete implementations

3. Implement Comprehensive Validation

Account validation should be thorough to prevent data inconsistencies:

public bool ValidateAccountCode(string accountCode, AccountType accountType)

{

if (string.IsNullOrWhiteSpace(accountCode))

return false;

// Account code should be numeric

if (!accountCode.All(char.IsDigit))

return false;

// Check that account code prefix matches account type

char expectedPrefix = GetExpectedPrefix(accountType);

return accountCode.Length > 0 && accountCode[0] == expectedPrefix;

}

4. Integrate with Financial Reporting

The chart of accounts should map accounts to financial statement lines for reporting:

- Balance sheet lines

- Income statement lines

- Cash flow statement lines

- Equity statement lines

Testing the Chart of Accounts Module

Comprehensive testing is crucial for a chart of accounts module:

- Unit Tests: Test individual components like account validation and balance calculation

- Integration Tests: Verify that components work together properly

- Business Rule Tests: Ensure business rules like “assets have debit balances” are enforced

- Persistence Tests: Confirm correct database interaction

Common Challenges and Solutions

When working with a chart of accounts module, you might encounter:

1. Account Code Standardization

Challenge: Different jurisdictions may have different account coding requirements.

Solution: Implement a flexible validation system that can be configured for different accounting standards.

2. Balance Calculation Performance

Challenge: Balance calculations for accounts with many transactions can be slow.

Solution: Implement caching strategies and consider storing period-end balances for faster reporting.

3. Account Hierarchies

Challenge: Supporting account hierarchies for reporting.

Solution: Implement a nested set model or closure table for efficient hierarchy querying.

Conclusion

A well-designed chart of accounts module is the foundation of a reliable accounting system. By following these implementation guidelines and understanding the core concepts, you can create a flexible, maintainable, and powerful chart of accounts that will serve as the backbone of your financial accounting application.

Remember that the chart of accounts is not just a technical construct—it should reflect the business needs and reporting requirements of the organization using the system. Taking time to properly design this module will pay dividends throughout the life of your application.

Repo

egarim/SivarErp: Open Source ERP

About Us

YouTube

https://www.youtube.com/c/JocheOjedaXAFXAMARINC

Our sites

Let’s discuss your XAF

This call/zoom will give you the opportunity to define the roadblocks in your current XAF solution. We can talk about performance, deployment or custom implementations. Together we will review you pain points and leave you with recommendations to get your app back in track

https://calendly.com/bitframeworks/bitframeworks-free-xaf-support-hour

Our free A.I courses on Udemy