by Joche Ojeda | Jan 30, 2026 | C#, dotnet

There is a familiar moment in every developer’s life.

Memory usage keeps creeping up.

The process never really goes down.

After hours—or days—the application feels heavier, slower, tired.

And the conclusion arrives almost automatically:

“The framework has a memory leak.”

“That component library is broken.”

“The GC isn’t doing its job.”

It’s a comforting explanation.

It’s also usually wrong.

Memory Leaks vs. Memory Retention

In managed runtimes like .NET, true memory leaks are rare.

The garbage collector is extremely good at reclaiming memory.

If an object is unreachable, it will be collected.

What most developers call a “memory leak” is actually

memory retention.

- Objects are still referenced

- So they stay alive

- Forever

From the GC’s point of view, nothing is wrong.

From your point of view, RAM usage keeps climbing.

Why Frameworks Are the First to Be Blamed

When you open a profiler and look at what’s alive, you often see:

- UI controls

- ORM sessions

- Binding infrastructure

- Framework services

So it’s natural to conclude:

“This thing is leaking.”

But profilers don’t answer why something is alive.

They only show that it is alive.

Framework objects are usually not the cause — they are just sitting at the

end of a reference chain that starts in your code.

The Classic Culprit: Bad Event Wiring

The most common “mirage leak” is caused by events.

The pattern

- A long-lived publisher (static service, global event hub, application-wide manager)

- A short-lived subscriber (view, view model, controller)

- A subscription that is never removed

That’s it. That’s the leak.

Why it happens

Events are references.

If the publisher lives for the lifetime of the process, anything it

references also lives for the lifetime of the process.

Your object doesn’t get garbage collected.

It becomes immortal.

The Immortal Object: When Short-Lived Becomes Eternal

An immortal object is an object that should be short-lived

but can never be garbage collected because it is still reachable from a GC

root.

Not because of a GC bug.

Not because of a framework leak.

But because our code made it immortal.

Static fields, singletons, global event hubs, timers, and background services

act as anchors. Once a short-lived object is attached to one of these, it

stops aging.

GC Root

└── static / singleton / service

└── Event, timer, or callback

└── Delegate or closure

└── Immortal object

└── Large object graph

From the GC’s perspective, everything is valid and reachable.

From your perspective, memory never comes back down.

A Retention Dependency Tree That Cannot Be Collected

GC Root

└── static GlobalEventHub.Instance

└── GlobalEventHub.DataUpdated (event)

└── delegate → CustomerViewModel.OnDataUpdated

└── CustomerViewModel

└── ObjectSpace / DbContext

└── IdentityMap / ChangeTracker

└── Customer, Order, Invoice, ...

What you see in the memory dump:

- thousands of entities

- ORM internals

- framework objects

What actually caused it:

- one forgotten event unsubscription

The Lambda Trap (Even Worse, Because It Looks Innocent)

The code

public CustomerViewModel(GlobalEventHub hub)

{

hub.DataUpdated += (_, e) =>

{

RefreshCustomer(e.CustomerId);

};

}

This lambda captures this implicitly.

The compiler creates a hidden closure that keeps the instance alive.

“But I Disposed the Object!”

Disposal does not save you here.

- Dispose does not remove event handlers

- Dispose does not break static references

- Dispose does not stop background work automatically

IDisposable is a promise — not a magic spell.

Leak-Hunting Checklist

Reference Roots

- Are there static fields holding objects?

- Are singletons referencing short-lived instances?

- Is a background service keeping references alive?

Events

- Are subscriptions always paired with unsubscriptions?

- Are lambdas hiding captured references?

Timers & Async

- Are timers stopped and disposed?

- Are async loops cancellable?

Profiling

- Follow GC roots, not object counts

- Inspect retention paths

- Ask: who is holding the reference?

Final Thought

Frameworks rarely leak memory.

We do.

Follow the references.

Trust the GC.

Question your wiring.

That’s when the mirage finally disappears.

by Joche Ojeda | Jan 8, 2026 | C#, XAF

Async/await in C# is often described as “non-blocking,” but that description hides an important detail:

await is not just about waiting — it is about where execution continues afterward.

Understanding that single idea explains:

- why deadlocks happen,

- why

ConfigureAwait(false) exists,

- and why it *reduces* damage without fixing the root cause.

This article is not just theory. It’s written because this exact class of problem showed up again in real production code during the first week of 2026 — and it took a context-level fix to resolve it.

The Hidden Mechanism: Context Capture

When you await a task, C# does two things:

- It pauses the current method until the awaited task completes.

- It captures the current execution context (if one exists) so the continuation can resume there.

That context might be:

- a UI thread (WPF, WinForms, MAUI),

- a request context (classic ASP.NET),

- or no special context at all (ASP.NET Core, console apps).

This default behavior is intentional. It allows code like this to work safely:

var data = await LoadAsync();

MyLabel.Text = data.Name; // UI-safe continuation

But that same mechanism becomes dangerous when async code is blocked synchronously.

The Root Problem: Blocking on Async

Deadlocks typically appear when async code is forced into a synchronous shape:

var result = GetDataAsync().Result; // or .Wait()

What happens next:

- The calling thread blocks, waiting for the async method to finish.

- The async method completes its awaited operation.

- The continuation tries to resume on the original context.

- That context is blocked.

- Nothing can proceed.

💥 Deadlock.

This is not an async bug. This is a context dependency cycle.

The Blast Radius Concept

Blocking on async is the explosion.

The blast radius is how much of the system is taken down with it.

Full blast (default await)

- Continuation *requires* the blocked context

- The async operation cannot complete

- The caller never unblocks

- Everything stops

Reduced blast (ConfigureAwait(false))

- Continuation does not require the original context

- It resumes on a thread pool thread

- The async operation completes

- The blocking call unblocks

The original mistake still exists — but the damage is contained.

The real fix is “don’t block on async,”

but ConfigureAwait(false) reduces the blast radius when someone does.

What ConfigureAwait(false) Actually Does

await SomeAsyncOperation().ConfigureAwait(false);

This tells the runtime:

“I don’t need to resume on the captured context. Continue wherever it’s safe to do so.”

Important clarifications:

- It does not make code faster by default

- It does not make code parallel

- It does not remove the need for proper async flow

- It only removes context dependency

Why This Matters in Real Code

Async code rarely exists in isolation.

A method often awaits another method, which awaits another:

await AAsync();

await BAsync();

await CAsync();

If any method in that chain requires a specific context, the entire chain becomes context-bound.

That is why:

- library code must be careful,

- deep infrastructure layers must avoid context assumptions,

- and UI layers must be explicit about where context is required.

When ConfigureAwait(false) Is the Right Tool

Use it when all of the following are true:

- The method does not interact with UI state

- The method does not depend on a request context

- The method is infrastructure, library, or backend logic

- The continuation does not care which thread resumes it

This is especially true for:

- NuGet packages

- shared libraries

- data access layers

- network and IO pipelines

What It Is Not

ConfigureAwait(false) is not:

- a fix for bad async usage

- a substitute for proper async flow

- a reason to block on tasks

- something to blindly apply everywhere

It is a damage-control tool, not a cure.

A Real Incident: When None of the Usual Fixes Worked

First week of 2026.

The first task I had with the programmers in my office was to investigate a problem in a trading block. The symptoms looked like a classic async issue: timing bugs, inconsistent behavior, and freezes that felt “await-shaped.”

We did what experienced .NET teams typically do when async gets weird:

- Reviewed the full async/await chain end-to-end

- Double-checked the source code carefully (everything looked fine)

- Tried the usual “tools people reach for” under pressure:

.Wait().GetAwaiter().GetResult()- wrapping in

Task.Run(...)

- adding

ConfigureAwait(false)

- mixing combinations of those approaches

None of it reliably fixed the problem.

At that point it stopped being a “missing await” story. It became a “the model is right but reality disagrees” story.

One of the programmers, Daniel, and I went deeper. I found myself mentally replaying every async pattern I know — especially because I’ve written async-heavy code myself, including library work like SyncFramework, where I synchronize databases and deal with long-running operations.

That’s the moment where this mental model matters: it forces you to stop treating await like syntax and start treating it like mechanics.

The Actual Root Cause: It Was the Context

In the end, the culprit wasn’t which pattern we used — it was where the continuation was allowed to run.

This application was built on DevExpress XAF. In this environment, the “correct” continuation behavior is often tied to XAF’s own scheduling and application lifecycle rules. XAF provides a mechanism to run code in its synchronization context — for example using BlazorApplication.InvokeAsync, which ensures that continuations run where the framework expects.

Once we executed the problematic pipeline through XAF’s synchronization context, the issue was solved.

No clever pattern. No magical await. No extra parallelism.

Just: the right context.

And this is not unique to XAF. Similar ideas exist in:

- Windows Forms (UI thread affinity + SynchronizationContext)

- WPF (Dispatcher context)

- Any framework that requires work to resume on a specific thread/context

Why I’m Writing This

What I wanted from this experience is simple: don’t forget it.

Because what makes this kind of incident dangerous is that it looks like a normal async bug — and the internet is full of “four fixes” people cycle through:

- add/restore missing

await

- use

.Wait() / .Result

- wrap in

Task.Run()

- use

ConfigureAwait(false)

Sometimes those are relevant. Sometimes they’re harmful. And sometimes… they’re all beside the point.

In our case, the missing piece was framework context — and once you see that, you realize why the “blast radius” framing is so useful:

- Blocking is the explosion.

ConfigureAwait(false) contains damage when someone blocks.- If a framework requires a specific synchronization context, the fix may be to supply the correct context explicitly.

That’s what happened here. And that’s why I’m capturing it as live knowledge, not just documentation.

The Mental Model to Keep

- Async bugs are often context bugs

- Blocking creates the explosion

- Context capture determines the blast radius

ConfigureAwait(false) limits the damage- Proper async flow prevents the explosion entirely

- Frameworks may require their own synchronization context

- Correct async code can still fail in the wrong context

Async is not just about tasks. It’s about where your code is allowed to continue.

by Joche Ojeda | Dec 23, 2025 | ADO, ADO.NET, C#

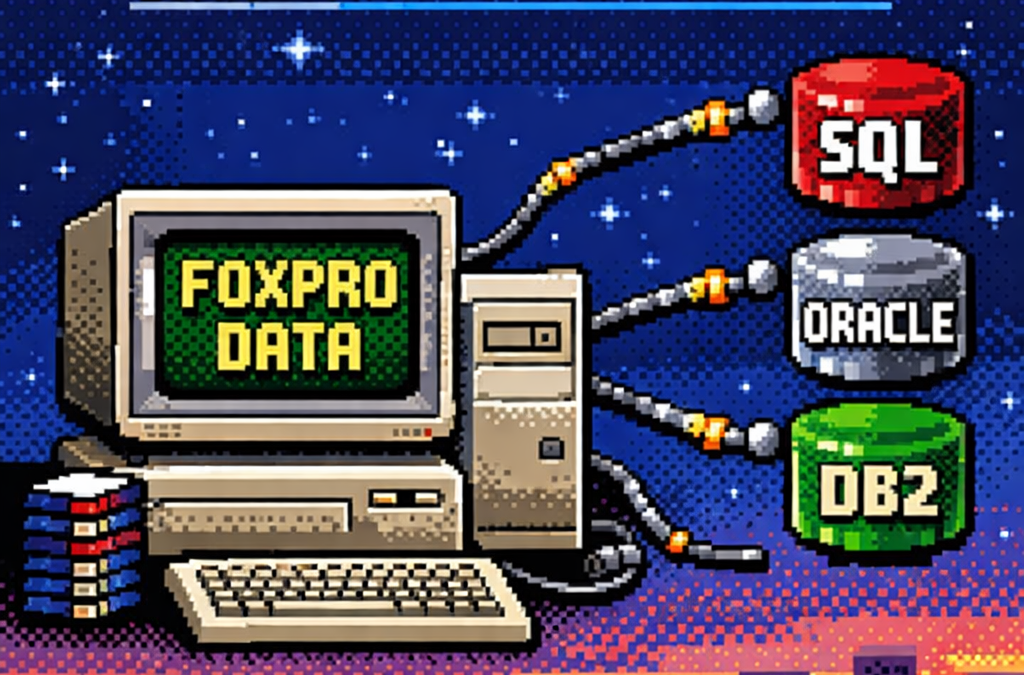

When I started working with computers, one of the tools that shaped my way of thinking as a developer was FoxPro.

At the time, FoxPro felt like a complete universe: database engine, forms, reports, and business logic all integrated into a single environment.

Looking back, FoxPro was effectively an application framework from the past—long before that term became common.

Accessing FoxPro data usually meant choosing between two paths:

- Direct FoxPro access – fast, tightly integrated, and fully aware of FoxPro’s features

- ODBC – a standardized way to access the data from outside the FoxPro ecosystem

This article focuses on that second option.

What Is ODBC?

ODBC (Open Database Connectivity) is a standardized API for accessing databases.

Instead of applications talking directly to a specific database engine, they talk to an ODBC driver,

which translates generic database calls into database-specific commands.

The promise was simple:

One API, many databases.

And for its time, this was revolutionary.

Supported Operating Systems and Use Cases

ODBC is still relevant today and supported across major platforms:

- Windows – native support, mature tooling

- Linux – via unixODBC and vendor drivers

- macOS – supported through driver managers

Typical use cases include:

- Legacy systems that must remain stable

- Reporting and BI tools

- Data migration and ETL pipelines

- Cross-vendor integrations

- Long-lived enterprise systems

ODBC excels where interoperability matters more than elegance.

The Lowest Common Denominator Problem

Although ODBC is a standard, it does not magically unify databases.

Each database has its own:

- SQL dialect

- Data types

- Functions

- Performance characteristics

ODBC standardizes access, not behavior.

You can absolutely open an ODBC connection and still:

- Call native database functions

- Use vendor-specific SQL

- Rely on engine-specific behavior

This makes ODBC flexible—but not truly database-agnostic.

ODBC vs True Abstraction Layers

This is where ODBC differs from ORMs or persistence frameworks that aim for full abstraction.

- ODBC: Gives you a common door and does not prevent database-specific usage

- ORM-style frameworks: Try to hide database differences and enforce a common conceptual model

ODBC does not protect you from database specificity—it permits it.

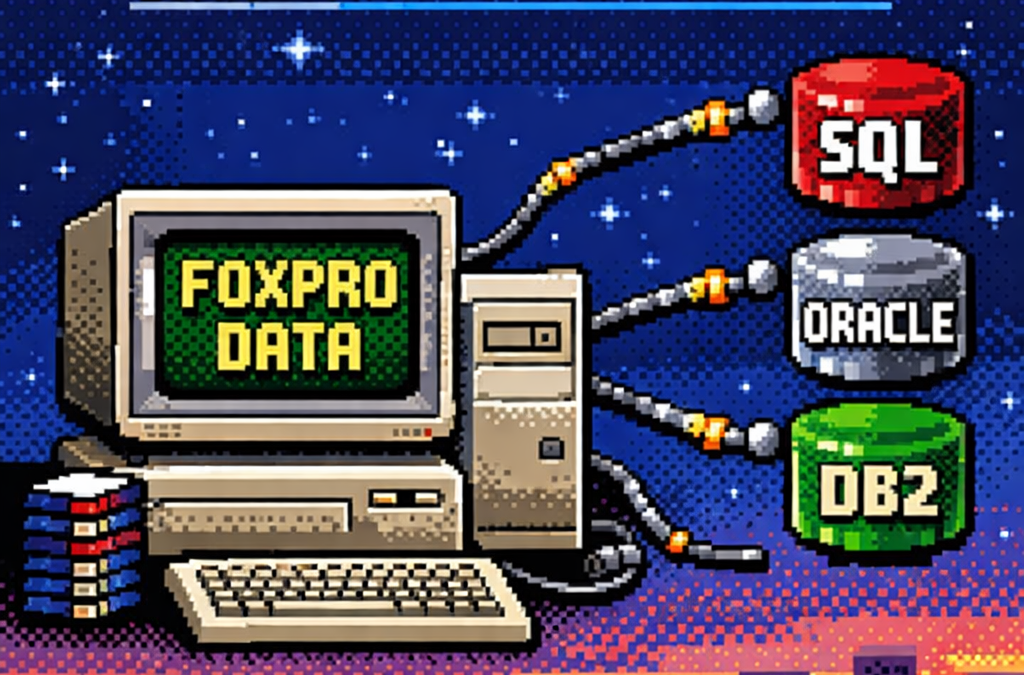

ODBC in .NET: Avoiding Native Database Dependencies

This is an often-overlooked advantage of ODBC, especially in .NET applications.

ADO.NET is interface-driven:

IDbConnectionIDbCommandIDataReader

However, each database requires its own concrete provider:

- SQL Server

- Oracle

- DB2

- Pervasive

- PostgreSQL

- MySQL

Each provider introduces:

- Native binaries

- Vendor SDKs

- Version compatibility issues

- Deployment complexity

Your code may be abstract — your deployment is not.

ODBC as a Binary Abstraction Layer

When using ODBC in .NET, your application depends on one provider only:

System.Data.Odbc

Database-specific dependencies are moved:

- Out of your application

- Into the operating system

- Into driver configuration

This turns ODBC into a dependency firewall.

Minimal .NET Example: ODBC vs Native Provider

Native ADO.NET Provider (Example: SQL Server)

using System.Data.SqlClient;

using var connection =

new SqlConnection("Server=.;Database=AppDb;Trusted_Connection=True;");

connection.Open();

Implications:

- Requires SQL Server client libraries

- Ties the binary to SQL Server

- Changing database = new provider + rebuild

ODBC Provider (Database-Agnostic Binary)

using System.Data.Odbc;

using var connection =

new OdbcConnection("DSN=AppDatabase");

connection.Open();

Implications:

- Same binary works for SQL Server, Oracle, DB2, etc.

- No vendor-specific DLLs in the app

- Database choice is externalized

The SQL inside the connection may still be database-specific — but your application binary is not.

Trade-Offs (And Why They’re Acceptable)

Using ODBC means:

- Fewer vendor-specific optimizations

- Possible performance differences

- Reliance on driver quality

But in exchange, you gain:

- Simpler deployments

- Easier migrations

- Longer application lifespan

- Reduced vendor lock-in

For many enterprise systems, this is a strategic win.

What’s Next – Phase 2: Customer Polish

Phase 1 is about making it work.

Phase 2 is about making it survivable for customers.

In Phase 2, ODBC shines by enabling:

- Zero-code database switching

- Cleaner installers

- Fewer runtime surprises

- Support for customer-controlled environments

- Reduced friction in on-prem deployments

This is where architecture meets reality.

Customers don’t care how elegant your abstractions are — they care that your software runs on their infrastructure without drama.

Project References

Minimal and explicit:

System.Data

System.Data.Odbc

Optional (native providers, when required):

System.Data.SqlClient

Oracle.ManagedDataAccess

IBM.Data.DB2

ODBC allows these to become optional, not mandatory.

Closing Thought

ODBC never promised purity.

It promised compatibility.

Just like FoxPro once gave us everything in one place, ODBC gave us a way out — without burning everything down.

Decades later, that trade-off still matters.

by Joche Ojeda | May 12, 2025 | C#, SivarErp

Welcome back to our ERP development series! In previous days, we’ve covered the foundational architecture, database design, and core entity structures for our accounting system. Today, we’re tackling an essential but often overlooked aspect of any enterprise software: data import and export capabilities.

Why is this important? Because no enterprise system exists in isolation. Companies need to move data between systems, migrate from legacy software, or simply handle batch data operations. In this article, we’ll build robust import/export services for the Chart of Accounts, demonstrating principles you can apply to any part of your ERP system.

The Importance of Data Exchange

Before diving into the code, let’s understand why dedicated import/export functionality matters:

- Data Migration – When companies adopt your ERP, they need to transfer existing data

- System Integration – ERPs need to exchange data with other business systems

- Batch Processing – Accountants often prepare data in spreadsheets before importing

- Backup & Transfer – Provides a simple way to backup or transfer configurations

- User Familiarity – Many users are comfortable working with CSV files

CSV (Comma-Separated Values) is our format of choice because it’s universally supported and easily edited in spreadsheet applications like Excel, which most business users are familiar with.

Our Implementation Approach

For our Chart of Accounts module, we’ll create:

- A service interface defining import/export operations

- A concrete implementation handling CSV parsing/generation

- Unit tests verifying all functionality

Our goal is to maintain clean separation of concerns, robust error handling, and clear validation rules.

Defining the Interface

First, we define a clear contract for our import/export service:

/// <summary>

/// Interface for chart of accounts import/export operations

/// </summary>

public interface IAccountImportExportService

{

/// <summary>

/// Imports accounts from a CSV file

/// </summary>

/// <param name="csvContent">Content of the CSV file as a string</param>

/// <param name="userName">User performing the operation</param>

/// <returns>Collection of imported accounts and any validation errors</returns>

Task<(IEnumerable<IAccount> ImportedAccounts, IEnumerable<string> Errors)> ImportFromCsvAsync(string csvContent, string userName);

/// <summary>

/// Exports accounts to a CSV format

/// </summary>

/// <param name="accounts">Accounts to export</param>

/// <returns>CSV content as a string</returns>

Task<string> ExportToCsvAsync(IEnumerable<IAccount> accounts);

}

Notice how we use C# tuples to return both the imported accounts and any validation errors from the import operation. This gives callers full insight into the operation’s results.

Implementing CSV Import

The import method is the more complex of the two, requiring:

- Parsing and validating the CSV structure

- Converting CSV data to domain objects

- Validating the created objects

- Reporting any errors along the way

Here’s our implementation approach:

public async Task<(IEnumerable<IAccount> ImportedAccounts, IEnumerable<string> Errors)> ImportFromCsvAsync(string csvContent, string userName)

{

List<AccountDto> importedAccounts = new List<AccountDto>();

List<string> errors = new List<string>();

if (string.IsNullOrEmpty(csvContent))

{

errors.Add("CSV content is empty");

return (importedAccounts, errors);

}

try

{

// Split the CSV into lines

string[] lines = csvContent.Split(new[] { "\r\n", "\r", "\n" }, StringSplitOptions.RemoveEmptyEntries);

if (lines.Length <= 1)

{

errors.Add("CSV file contains no data rows");

return (importedAccounts, errors);

}

// Assume first line is header

string[] headers = ParseCsvLine(lines[0]);

// Validate headers

if (!ValidateHeaders(headers, errors))

{

return (importedAccounts, errors);

}

// Process data rows

for (int i = 1; i < lines.Length; i++)

{

string[] fields = ParseCsvLine(lines[i]);

if (fields.Length != headers.Length)

{

errors.Add($"Line {i + 1}: Column count mismatch. Expected {headers.Length}, got {fields.Length}");

continue;

}

var account = CreateAccountFromCsvFields(headers, fields);

// Validate account

if (!_accountValidator.ValidateAccount(account))

{

errors.Add($"Line {i + 1}: Account validation failed for account {account.AccountName}");

continue;

}

// Set audit information

_auditService.SetCreationAudit(account, userName);

importedAccounts.Add(account);

}

return (importedAccounts, errors);

}

catch (Exception ex)

{

errors.Add($"Error importing CSV: {ex.Message}");

return (importedAccounts, errors);

}

}

Key aspects of this implementation:

- Early validation – We quickly detect and report basic issues like empty input

- Row-by-row processing – Each line is processed independently, allowing partial success

- Detailed error reporting – We collect specific errors with line numbers

- Domain validation – We apply business rules from

AccountValidator

- Audit trail – We set audit fields for each imported account

The ParseCsvLine method handles the complexities of CSV parsing, including quoted fields that may contain commas:

private string[] ParseCsvLine(string line)

{

List<string> fields = new List<string>();

bool inQuotes = false;

int startIndex = 0;

for (int i = 0; i < line.Length; i++)

{

if (line[i] == '"')

{

inQuotes = !inQuotes;

}

else if (line[i] == ',' && !inQuotes)

{

fields.Add(line.Substring(startIndex, i - startIndex).Trim().TrimStart('"').TrimEnd('"'));

startIndex = i + 1;

}

}

// Add the last field

fields.Add(line.Substring(startIndex).Trim().TrimStart('"').TrimEnd('"'));

return fields.ToArray();

}

Implementing CSV Export

The export method is simpler, converting domain objects to CSV format:

public Task<string> ExportToCsvAsync(IEnumerable<IAccount> accounts)

{

if (accounts == null || !accounts.Any())

{

return Task.FromResult(GetCsvHeader());

}

StringBuilder csvBuilder = new StringBuilder();

// Add header

csvBuilder.AppendLine(GetCsvHeader());

// Add data rows

foreach (var account in accounts)

{

csvBuilder.AppendLine(GetCsvRow(account));

}

return Task.FromResult(csvBuilder.ToString());

}

We take special care to handle edge cases like null or empty collections, making the API robust against improper usage.

Testing the Implementation

Our test suite verifies both the happy paths and various error conditions:

- Import validation – Tests for empty content, missing headers, etc.

- Export formatting – Tests for proper CSV generation, handling of special characters

- Round-trip integrity – Tests exporting and re-importing preserves data integrity

For example, here’s a round-trip test to verify data integrity:

[Test]

public async Task RoundTrip_ExportThenImport_PreservesAccounts()

{

// Arrange

var originalAccounts = new List<IAccount>

{

new AccountDto

{

Id = Guid.NewGuid(),

AccountName = "Cash",

OfficialCode = "11000",

AccountType = AccountType.Asset,

// other properties...

},

new AccountDto

{

Id = Guid.NewGuid(),

AccountName = "Accounts Receivable",

OfficialCode = "12000",

AccountType = AccountType.Asset,

// other properties...

}

};

// Act

string csv = await _importExportService.ExportToCsvAsync(originalAccounts);

var (importedAccounts, errors) = await _importExportService.ImportFromCsvAsync(csv, "Test User");

// Assert

Assert.That(errors, Is.Empty);

Assert.That(importedAccounts.Count(), Is.EqualTo(originalAccounts.Count));

// Check first account

var firstOriginal = originalAccounts[0];

var firstImported = importedAccounts.First();

Assert.That(firstImported.AccountName, Is.EqualTo(firstOriginal.AccountName));

Assert.That(firstImported.OfficialCode, Is.EqualTo(firstOriginal.OfficialCode));

Assert.That(firstImported.AccountType, Is.EqualTo(firstOriginal.AccountType));

// Check second account similarly...

}

Integration with the Broader System

This service isn’t meant to be used in isolation. In a complete ERP system, you’d typically:

- Add a controller to expose these operations via API endpoints

- Create UI components for file upload/download

- Implement progress reporting for larger imports

- Add transaction support to make imports atomic

- Include validation rules specific to your business domain

Design Patterns and Best Practices

Our implementation exemplifies several important patterns:

- Interface Segregation – The service has a focused, cohesive purpose

- Dependency Injection – We inject the

IAuditService rather than creating it

- Early Validation – We validate input before processing

- Detailed Error Reporting – We collect and return specific errors

- Defensive Programming – We handle edge cases and exceptions gracefully

Future Extensions

This pattern can be extended to other parts of your ERP system:

- Customer/Vendor Data – Import/export contact information

- Inventory Items – Handle product catalog updates

- Journal Entries – Process batch financial transactions

- Reports – Export financial data for external analysis

Conclusion

Data import/export capabilities are a critical component of any enterprise system. They bridge the gap between systems, facilitate migration, and support batch operations. By implementing these services with careful error handling and validation, we’ve added significant value to our ERP system.

In the next article, we’ll explore building financial reporting services to generate balance sheets, income statements, and other critical financial reports from our accounting data.

Stay tuned, and happy coding!

About Us

YouTube

https://www.youtube.com/c/JocheOjedaXAFXAMARINC

Our sites

Let’s discuss your XAF

This call/zoom will give you the opportunity to define the roadblocks in your current XAF solution. We can talk about performance, deployment or custom implementations. Together we will review you pain points and leave you with recommendations to get your app back in track

https://calendly.com/bitframeworks/bitframeworks-free-xaf-support-hour

Our free A.I courses on Udemy

by Joche Ojeda | Mar 5, 2025 | C#, dotnet, Uno Platform

Exploring the Uno Platform: Handling Unsafe Code in Multi-Target Applications

This last weekend I wanted to do a technical experiment as I always do when I have some free time. I decided there was something new I needed to try and see if I could write about. The weekend turned out to be a beautiful surprise as I went back to test the Uno platform – a multi-OS, multi-target UI framework that generates mobile applications, desktop applications, web applications, and even Linux applications.

The idea of Uno is a beautiful concept, but for a long time, the tooling wasn’t quite there. I had made it work several times in the past, but after an update or something in Visual Studio, the setup would break and applications would become basically impossible to compile. That seems to no longer be the case!

Last weekend, I set up Uno on two different computers: my new Surface laptop with an ARM type of processor (which can sometimes be tricky for some tools) and my old MSI with an x64 type of processor. I was thrilled that the setup was effortless on both machines.

After the successful setup, I decided to download the entire Uno demo repository and start trying out the demos. However, for some reason, they didn’t compile. I eventually realized there was a problem with generated code during compilation time that turned out to be unsafe code. Here are my findings about how to handle the unsafe code that is generated.

AllowUnsafeBlocks Setting in Project File

I discovered that this setting was commented out in the Navigation.csproj file:

<!--<AllowUnsafeBlocks>true</AllowUnsafeBlocks>-->

When uncommented, this setting allows the use of unsafe code blocks in your .NET 8 Uno Platform project. To enable unsafe code, you need to remove the comment markers from this line in your project file.

Why It’s Needed

The <AllowUnsafeBlocks>true</AllowUnsafeBlocks> setting is required whenever you want to use “unsafe” code in C#. By default, C# is designed to be memory-safe, preventing direct memory manipulation that could lead to memory corruption, buffer overflows, or security vulnerabilities. When you add this setting to your project file, you’re explicitly telling the compiler to allow portions of code marked with the unsafe keyword.

Unsafe code lets you work with pointers and perform direct memory operations, which can be useful for:

- Performance-critical operations

- Interoperability with native code

- Direct memory manipulation

What Makes Code “Unsafe”

Code is considered “unsafe” when it bypasses .NET’s memory safety guarantees. Specifically, unsafe code includes:

- Pointer operations: Using the * and -> operators with memory addresses

- Fixed statements: Pinning managed objects in memory so their addresses don’t change during garbage collection

- Sizeof operator: Getting the size of a type in bytes

- Stackalloc keyword: Allocating memory on the stack instead of the heap

Example of Unsafe Code

Here’s an example of unsafe code that might be generated:

unsafe

{

int[] numbers = new int[] { 10, 20, 30, 40, 50 };

// UNSAFE: Pinning an array in memory and getting direct pointer

fixed (int* pNumbers = numbers)

{

// UNSAFE: Pointer declaration and manipulation

int* p = pNumbers;

// UNSAFE: Dereferencing pointers to modify memory directly

*p = *p + 5;

*(p + 1) = *(p + 1) + 5;

}

}

Why Use Unsafe Code?

There are several legitimate reasons to use unsafe code:

- Performance optimization: For extremely performance-critical sections where you need to eliminate overhead from bounds checking or other safety features.

- Interoperability: When interfacing with native libraries or system APIs that require pointers.

- Low-level operations: For systems programming tasks that require direct memory manipulation, like implementing custom memory managers.

- Hardware access: When working directly with device drivers or memory-mapped hardware.

- Algorithms requiring pointer arithmetic: Some specialized algorithms are most efficiently implemented using pointer operations.

Risks and Considerations

Using unsafe code comes with significant responsibilities:

- You bypass the runtime’s safety checks, so errors can cause application crashes or security vulnerabilities

- Memory leaks are possible if you allocate unmanaged memory and don’t free it properly

- Your code becomes less portable across different .NET implementations

- Debugging unsafe code is more challenging

In general, you should only use unsafe code when absolutely necessary and isolate it in small, well-tested sections of your application.

In conclusion, I’m happy to see that the Uno platform has matured significantly. While there are still some challenges like handling unsafe generated code, the setup process has become much more reliable. If you’re looking to develop truly cross-platform applications with a single codebase, Uno is worth exploring – just remember to uncomment that AllowUnsafeBlocks setting if you run into compilation issues!

by Joche Ojeda | Mar 2, 2025 | C#, System Theory

This past week, I have been working on a prototype for a wizard component. As you might know, in computer interfaces, wizard components (or multi-step forms) allow users to navigate through a finite number of steps or pages until they reach the end. Wizards are particularly useful because they don’t overwhelm users with too many choices at once, effectively minimizing the number of decisions a user needs to make at any specific moment.

The current prototype is created using XAF from DevExpress. If you follow this blog, you probably know that I’m a DevExpress MVP, and I wanted to use their tools to create this prototype.

I’ve built wizard components before, but mostly in a rush. Those previous implementations had the wizard logic hardcoded directly inside the UI components, with no separation between the UI and the underlying logic. While they worked, they were quite messy. This time, I wanted to take a more structured approach to creating a wizard component, so here are a few of my findings. Most of this might seem obvious, but sometimes it’s hard to see the forest for the trees when you’re sitting in front of the computer writing code.

Understanding the Core Concept: State Machines

To create an effective wizard component, you need to understand several underlying concepts. The idea of a wizard is actually rooted in system theory and computer science—it’s essentially an implementation of what’s called a state machine or finite state machine.

Theory of a State Machine

A state machine is the same as a finite state machine (FSM). Both terms refer to a computational model that describes a system existing in one of a finite number of states at any given time.

A state machine (or FSM) consists of:

- States: Distinct conditions the system can be in

- Transitions: Rules for moving between states

- Events/Inputs: Triggers that cause transitions

- Actions: Operations performed when entering/exiting states or during transitions

The term “finite” emphasizes that there’s a limited, countable number of possible states. This finite nature is crucial as it makes the system predictable and analyzable.

State machines come in several variants:

- Deterministic FSMs (one transition per input)

- Non-deterministic FSMs (multiple possible transitions per input)

- Mealy machines (outputs depend on state and input)

- Moore machines (outputs depend only on state)

They’re widely used in software development, hardware design, linguistics, and many other fields because they make complex behavior easier to visualize, implement, and debug. Common examples include traffic lights, UI workflows, network protocols, and parsers.

In practical usage, when someone refers to a “state machine,” they’re almost always talking about a finite state machine.

Implementing a Wizard State Machine

Here’s an implementation of a wizard state machine that separates the logic from the UI:

public class WizardStateMachineBase

{

readonly List<WizardPage> _pages;

int _currentIndex;

public WizardStateMachineBase(IEnumerable<WizardPage> pages)

{

_pages = pages.OrderBy(p => p.Index).ToList();

_currentIndex = 0;

}

public event EventHandler<StateTransitionEventArgs> StateTransition;

public WizardPage CurrentPage => _pages[_currentIndex];

public virtual bool MoveNext()

{

if (_currentIndex < _pages.Count - 1) { var args = new StateTransitionEventArgs(CurrentPage, _pages[_currentIndex + 1]); OnStateTransition(args); if (!args.Cancel) { _currentIndex++; return true; } } return false; } public virtual bool MovePrevious() { if (_currentIndex > 0)

{

var args = new StateTransitionEventArgs(CurrentPage, _pages[_currentIndex - 1]);

OnStateTransition(args);

if (!args.Cancel)

{

_currentIndex--;

return true;

}

}

return false;

}

protected virtual void OnStateTransition(StateTransitionEventArgs e)

{

StateTransition?.Invoke(this, e);

}

}

public class StateTransitionEventArgs : EventArgs

{

public WizardPage CurrentPage { get; }

public WizardPage NextPage { get; }

public bool Cancel { get; set; }

public StateTransitionEventArgs(WizardPage currentPage, WizardPage nextPage)

{

CurrentPage = currentPage;

NextPage = nextPage;

Cancel = false;

}

}

public class WizardPage

{

public int Index { get; set; }

public string Title { get; set; }

public string Description { get; set; }

public bool IsRequired { get; set; } = true;

public bool IsCompleted { get; set; }

// Additional properties specific to your wizard implementation

public object Content { get; set; }

public WizardPage(int index, string title)

{

Index = index;

Title = title;

}

public virtual bool Validate()

{

// Default implementation assumes page is valid

// Override this method in derived classes to provide specific validation logic

return true;

}

}

Benefits of This Approach

As you can see, by defining a state machine, you significantly narrow down the implementation possibilities. You solve the problem of “too many parts to consider” – questions like “How do I start?”, “How do I control the state?”, “Should the state be in the UI or a separate class?”, and so on. These problems can become really complicated, especially if you don’t centralize the state control.

This simple implementation of a wizard state machine shows how to centralize control of the component’s state. By separating the state management from the UI components, we create a cleaner, more maintainable architecture.

The WizardStateMachineBase class manages the collection of pages and handles navigation between them, while the StateTransitionEventArgs class provides a mechanism to cancel transitions if needed (for example, if validation fails). The newly added WizardPage class encapsulates all the information needed for each step in the wizard.

What’s Next?

The next step will be to control how the visual components react to the state of the machine – essentially connecting our state machine to the UI layer. This will include handling the display of the current page content, updating navigation buttons (previous/next/finish), and possibly showing progress indicators. I’ll cover this UI integration in my next post.

By following this pattern, you can create wizard interfaces that are not only user-friendly but also maintainable and extensible from a development perspective.

Source Code

egarim/WizardStateMachineTest

About US

YouTube

https://www.youtube.com/c/JocheOjedaXAFXAMARINC

Our sites

https://www.bitframeworks.com

https://www.xari.io

https://www.xafers.training

Let’s discuss your XAF Support needs together! This 1-hour call/zoom will give you the opportunity to define the roadblocks in your current XAF solution

Schedule a meeting with us on this link